Hip dysplasia remains one of the most frequently discussed yet misunderstood topics in canine health. Despite decades of research and screening programmes, misconceptions persist about what hip scores actually mean, how genetics and environment interact, and what constitutes healthy hips. These misunderstandings matter because they influence breeding decisions, how puppies are raised, and which dogs are included in future breeding populations.

Hip dysplasia is widely treated as a binary problem: a dog either has “good hips” or it does not. That binary is as appealing as it also misleading: what looks like a clear-cut verdict is produced by combining many separate judgements into a single result. Decisions about how radiographs are taken, which anatomical features are emphasised, how findings are summarised, and how results are reported all shape the final score.

When these layers are overlooked, simplified outcomes are mistaken for biological truths. This article examines some of the most persistent myths that arise from that misunderstanding. Before addressing them, it is worth remembering one key point: hip scores do not simply describe how hips look – they also reflect how complex information has been interpreted according to agreed conventions.

A shorter version of this article was originally written for the Polish Hunting Spaniel breed club magazine, PSM Bulletin.

Myth 1: Only “A” hips are healthy

Clear pass–fail categories feel reassuring, but they oversimplify how hip scores are constructed and what they represent.

Many people believe that only “A”-graded hips are truly healthy. Anything less is seen as implying dysfunction, pain, or unsuitability for breeding. This binary view isn’t supported by veterinary evidence or real-world outcomes. Hip health exists on a continuum, not a strict pass/fail system. The FCI grading method combines three different features: joint congruency, the Norberg angle, and visible signs of degeneration. This means the system conflates risk factors like joint laxity with actual outcomes such as arthritic change.

Radiographs show only bone shape at a single moment. They don’t reveal how the joint functions in motion or how well soft tissues support it. A dog with excellent X-rays may still develop problems if it has poor overall structure, carries excess weight, or lacks proper muscle conditioning. The letter grade reflects observable traits that correlate with risk, but doesn’t necessarily predict what happens to an individual dog. Treating “A” as the gold standard and all other grades as failures ignores this complexity and risks narrowing the gene pool based on a misunderstood metric. Hip-screening systems that reduce complex variation into simple categories drastically limit the functional diversity available for selection (1).

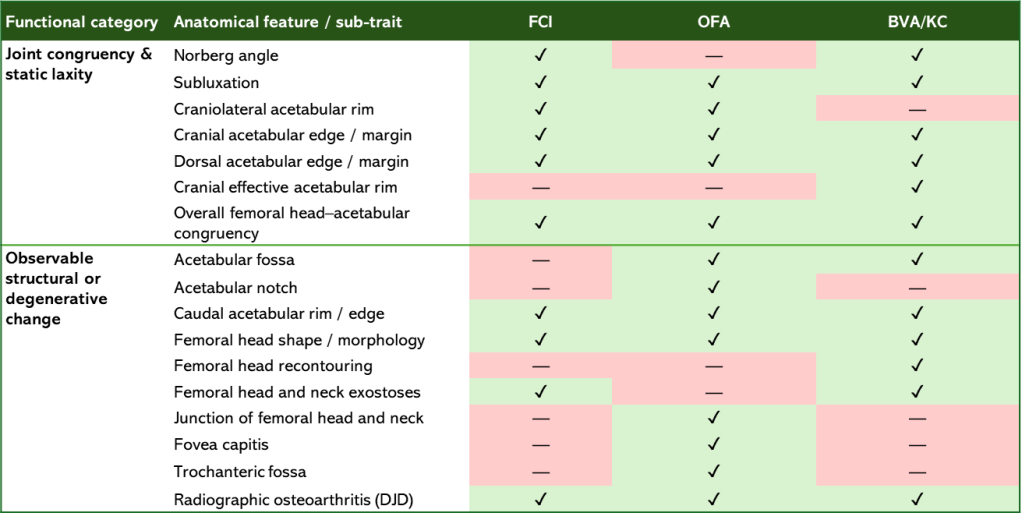

Although this section uses the FCI grading system as its primary example, the same conceptual limitation applies to other commonly used hip screening schemes, including OFA and BVA/KC. While these systems differ in format and scoring, they assess largely overlapping anatomical features and similarly combine indicators of joint laxity with visible structural or degenerative change into a single score or grade – click below for detailed information and a summary table.

Another important and often overlooked source of confusion is that the FCI grading framework is not implemented identically across member countries. In some countries, left and right hips are graded and reported separately (for example A/A), whereas in others a single official grade is issued based on the worse hip only. This variation complicates comparisons between dogs, datasets, and breeding populations, and reinforces the need to treat hip grades as context-dependent indicators rather than absolute measures of hip health.

These differences in scoring and reporting also affect how population-level research findings should be interpreted. Studies based on hip score data necessarily reflect the conventions of the screening system and country in which the data were collected. Whether scores are reported per hip or per dog, whether the worse hip determines classification, and how borderline cases are categorised all influence prevalence estimates, heritability calculations, and apparent trends over time. As a result, findings derived from one population or screening framework are not always directly transferable to another, even when the same nominal grading system is used.

Additional detail: how the FCI hip score is constructed

The Fédération Cynologique Internationale (FCI) hip score is a classic example of an aggregate trait. It combines multiple anatomical observations into a single grade intended to reflect overall hip status. In practice, the most influential component of the evaluation is joint incongruity (a largely subjective assessment) although veterinarians scoring the radiographs may also consider several other features.

Commonly evaluated indicators include the Norberg angle, visible joint subluxation, the shape and depth of the acetabulum, the position of the femoral head within the socket, and the presence of osteoarthritic change. These features describe a mixture of joint congruency, coverage, and structural adaptation. However, their relative importance in the final grade is not strictly standardised. Different evaluators may emphasise specific findings differently, which introduces unavoidable non-uniformity into the scoring process. Additionally, existing measures of laxity are technically demanding and influenced by positioning and magnification (48).

A further limitation is that the standard hip-extended ventrodorsal (HEVD) radiographic view used in FCI screening is relatively insensitive to detecting passive hip laxity. As a result, the score reflects how the joint appears under standardised positioning rather than how stable it may be under functional loading. It is also important to note that FCI implementation is not entirely uniform across member countries. In some countries, such as Finland, left and right hips are reported separately (e.g. A/A), whereas in many others a single grade based on the worse hip is issued. This difference alone can influence how results are interpreted and used in breeding decisions.

Several commonly used measures within the FCI system have also been criticised in the literature. The Norberg angle, while widely used as an indicator of subluxation and incongruity, is influenced by acetabular depth and has been shown to be a poor predictor of future osteoarthritis. The conventional cut-off value of 105 degrees separating “dysplastic” from “non-dysplastic” hips is somewhat arbitrary, and reproducibility can be low when evaluators do not apply identical measurement protocols. Other incongruity measures, such as the position of the femoral head centre relative to the dorsal acetabular edge, are closely correlated with the Norberg angle and therefore do not represent independent information which further limits how much additional certainty can be gained by combining multiple related measures.

Taken together, these features illustrate why the FCI score is best understood as a composite snapshot of joint appearance rather than a precise or exhaustive assessment of hip function or long-term clinical outcome.

Additional information on different schemes

Several hip dysplasia screening systems are used internationally. While they differ in scoring format and terminology, most evaluate broadly similar radiographic features and face the same underlying limitation: they assess joint morphology and secondary change at a single point in time, not joint function in motion.

The Orthopedic Foundation for Animals (OFA) uses the Hip-Extended Ventrodorsal (HEVD) radiographic view and assigns hips to one of seven categories: Excellent, Good, Fair, Borderline, Mild, Moderate, or Severe. Grading is based on the collective assessment of multiple anatomical features and those sub-traits reflect joint congruency, coverage, and the presence of degenerative change, rather than direct measures of stability or load tolerance.

The British Veterinary Association / Kennel Club (BVA/KC) used in the UK and several other countries, including Australia also relies on the HEVD view. Each hip is scored separately, with numerical values assigned to nine sub-traits. The total hip score is the sum of both hips, with higher scores indicating more severe deviation from the reference standard. As with other schemes, the final number is an aggregate of multiple anatomical observations rather than a direct prediction of clinical outcome.

One widely used system not covered above is PennHIP, which differs conceptually from FCI, OFA, and BVA schemes. PennHIP quantifies passive hip laxity using a distraction index, with the aim of estimating the risk of developing osteoarthritis rather than describing current joint appearance. While often presented as more objective, PennHIP still measures a surrogate marker (passive laxity under standardised conditions) and does not directly assess dynamic stability, neuromuscular control, or functional load management. Use of PennHIP requires specific training and certification, which limits its availability in many countries outside the US and Canada. It is also less widely recognised than other screening schemes, despite evidence suggesting it can be a useful predictive tool at the population level.

Despite surface differences, these schemes evaluate overlapping anatomical features and are best understood as population-level risk stratification tools. None can fully capture how an individual dog’s hips will perform over a lifetime shaped by structure, muscle development, bodyweight, and mechanical exposure.

Myth 2: Breeders alone determine a dog’s joint health

Genetics matter, but they explain only part of the outcome.

The assumption that hip health is purely inherited is an oversimplification. Many people believe that puppies from parents with healthy hips will automatically enjoy the same outcome, but this isn’t how inheritance works. Heritability estimates for hip dysplasia range from 0.1 to 0.6, depending on the breed and dataset (1, 2). A comprehensive 40-year study across 74 breeds found that only 22% of the variation in hip scores could be attributed to genetics alone (3). For a trait with such moderate heritability, relying solely on parents’ hip scores to predict offspring health is both slow and inefficient.

While selecting parents with sound hips remains important, what happens after a puppy is born can be just as critical. Even puppies from parents with excellent hip scores can develop joint issues if raised on slippery flooring, overfed, or given restricted movement.

Hip formation is a dynamic process, heavily influenced by mechanical forces and activity during early life. Between 6 and 12 weeks of age, puppies develop joint depth and congruity through neuromuscular activity (4, 5). Studies on genetically identical Labrador Retriever puppies raised in different environments showed significant differences in hip dysplasia severity, purely due to variations in early development and management (6). Environmental influences such as flooring, exercise, and body condition are powerful modifiers of hip dysplasia risk – in other words, even the best genetic potential can be compromised by poor rearing practices (5, 6, 7, 8) .

Breeders play a crucial role in testing and selecting healthy parents. However, owners hold equal, if not greater, influence during the critical growth stages. Healthy hips are not solely the result of good breeding (45). They are a shared responsibility between breeders and owners, shaped by both genetics and environment.

How effective have global HD screening programmes been?

The effectiveness of screening programmes for canine hip dysplasia has been mixed and varies considerably by country, breed, and the selection strategies used (45). Across many populations, the most consistent success has been a reduction in the most severe forms of the disease, while overall prevalence has often remained high (37). In other words, screening has been effective at preventing the worst outcomes, but less effective at eliminating hip dysplasia as a whole.

Sweden represents the most frequently cited example of long-term success. Over more than sixty years of screening, the prevalence of moderate and severe hip dysplasia has been reduced to below ten percent in most predisposed breeds. This progress is generally attributed to mandatory screening, open registries, and strong cultural norms favouring breeding only from unaffected dogs (40). Importantly, these results reflect not only the screening method itself, but also the way the data were used and shared.

By contrast, results from voluntary schemes have been more modest. Long-term monitoring by the Orthopedic Foundation for Animals in the United States shows a genetic improvement of approximately 16% of the phenotypic standard deviation over a 40-year period. However, the voluntary nature of reporting has introduced substantial bias: owners are over eight times more likely to submit radiographs of dogs with normal-appearing hips than of dogs with obvious dysplasia, which limits the accuracy of population-level estimates (3).

Outcomes also differ between breeds within the same country. Retrospective studies in the United Kingdom show steady improvement in popular breeds such as Labrador Retrievers and Golden Retrievers, although overall genetic progress has been described as slow due to weak selection pressure (41).

One of the most detailed evaluations of a national hip dysplasia control programme comes from Finland. In a retrospective analysis of more than 69,000 dogs across 22 breeds (42), researchers compared hip dysplasia prevalence in dogs born between 1988 and 1995 with data from earlier cohorts. In most breeds, no significant change in overall prevalence was observed. Some breeds, including English Cocker Spaniels, Golden Retrievers, Labrador Retrievers, and Rottweilers, showed a significant decrease. Others, such as Boxers, Dobermans, German Shepherd Dogs, and Rough Collies, showed a significant increase over the same period. In Flat-Coated Retrievers, overall prevalence increased even as the prevalence of severe disease declined.

Several structural limitations help explain these mixed results. Many programmes rely on the standard ventrodorsal hip-extended radiographic view, which can underestimate joint laxity, one of the primary risk factors for hip dysplasia (37). There is also significant variation between countries and kennel clubs with differences in data collection, enforcement, and transparency, as well as inconsistent use of advanced tools like EBVs (45) – in reality, the effectiveness of HD screening depends as much on governance and compliance as on the screening method itself.

In addition, selection based solely on an individual dog’s radiographic appearance is inherently inefficient. A dog with a normal phenotype may still carry and transmit genetic risk, while dogs with less favourable scores may produce healthier offspring depending on the genetic background of the mating. Genetic modelling suggests that selection based on Estimated Breeding Values, which incorporate information from relatives as well as the individual, can substantially improve the rate of progress (43). Looking further ahead, genomic selection using DNA markers may allow risk to be estimated earlier in life and without reliance on radiography, although this approach is still under development (39).

Taken together, these findings suggest that hip dysplasia screening is neither a failure nor a simple success. It works best when participation is broad, data are transparent, and selection decisions use population-level information rather than isolated scores. Where these conditions are not met, progress is slower and outcomes are more variable.

What early rearing environments in professional breeding systems look like

It is also worth remembering that much of what we know about hip dysplasia comes from dogs raised in highly controlled, professional breeding environments, where practical human priorities have historically shaped early-life conditions.

Recent research continues to reinforce the importance of early environmental conditions in shaping musculoskeletal development. Studies examining puppy movement and limb loading show that surface type, traction, and environmental complexity influence coordination, muscle development, and joint loading patterns during critical growth periods (9).

What is often left unstated is how closely much of the existing evidence reflects the realities of large-scale, professional breeding systems. In many commercial and service-dog programmes, whelping and rearing environments have historically prioritised hygiene, ease of cleaning, and disease control. The surfaces most compatible with those priorities are typically smooth, uniform, and low-friction. From a human management perspective, these choices are rational and practical. From a developmental perspective, however, they may limit opportunities for traction, varied loading, and early neuromuscular challenge.

This context matters because a substantial proportion of hip dysplasia research is derived from service-dog populations bred and raised in professional programmes. The environmental conditions common to those systems inevitably shape the data they produce. Understanding this does not invalidate the research, but it does help explain why environmental effects may be underestimated and why results from such populations do not always translate cleanly to dogs raised in more varied home or outdoor settings.

Myth 3: A “C” means the dog has unhealthy hips

Moderate scores are often mistaken for disease rather than variation.

Hip scores should be one part of a broader evaluation alongside structure, movement, temperament, and overall genetic contribution. A single letter doesn’t tell the whole story, and thoughtful breeding decisions often involve balancing multiple traits. The real goal is to avoid breeding dogs with D or E scores, where the risk of joint disease is significantly higher.

A “C” grade often reflects mild joint laxity without any signs of damage or degeneration. It is not a diagnosis, nor an automatic disqualifier. With good structure, lean body condition, appropriate conditioning, and careful pairings, dogs with C hips can lead long, active, pain-free lives and contribute positively to genetic diversity. In a developing breed such as the Polish Hunting Spaniel, discarding moderate scores without context risks removing excellent individuals, particularly females, from a limited gene pool.

One factor often overlooked in radiographic assessments is pelvic muscle mass. Adequate muscle development around the hip joint provides dynamic support, helping stabilise the femoral head within the socket during movement. Studies show that dogs with greater pelvic musculature are more likely to develop stable hips (10, 11, 12, 13, 14).

Early-life experiences also play a critical role. Exercise during the first three months, especially free movement on varied outdoor terrain, has been shown to reduce the risk of hip dysplasia. Puppies given opportunities to move off leash on grass and uneven ground tend to develop better muscle tone and neuromuscular coordination, both of which contribute to hip stability (15, 16).

Growth patterns also matter. Experimental studies have shown that increased birth weight alone can be sufficient to alter the course of hip development and result in measurable degenerative changes in adulthood, even in the absence of other risk factors (17). This highlights how early biological and environmental influences can shape long-term joint outcomes independently of radiographic appearance in maturity.

This issue is particularly relevant when evaluating female dogs. A large-scale study with more than 5000 dogs from The Seeing Eye, a philanthropic organisation with a large database of guide dogs that are routinely assessed for hypermobility of the hip joint, found that female dogs are 3.5 times more likely to exhibit joint hypermobility than males (38) – a difference that reflects normal biological variation rather than disease. Factors such as collagen composition, ligament elasticity, and pelvic mechanics contribute to this increased flexibility. Joint hypermobility is common among certain groups of human athletes, where a greater range of motion can provide biomechanical advantages rather than limitations.

Female dogs are therefore statistically more likely to receive a lower hip score – not necessarily because they have unhealthy hips, but because their joints are more compliant. If all dogs are judged using male-based biomechanical expectations, healthy females may be systematically penalised. Over time, this risks narrowing the gene pool in ways that could compromise the breed’s long-term health.

Myth 4: Hip scores are precise, objective facts

Numbers look definitive, even when they summarise judgement and context.

Hip scores often seem to offer certainty in the form of a single number or letter that captures the exact quality of a dog’s hips. In reality, they represent an interpretation of multiple variables. Radiographic assessments depend on the dog’s positioning, the depth of sedation, the radiographic technique used, and the evaluator’s experience. Each of these factors introduces potential variation. The most common scoring systems, including FCI, BVA, and OFA, combine several visual criteria, such as joint congruency, the Norberg angle, and visible signs of arthrosis. Even small differences in positioning or measurement can change the final grade (17, 18, 19).

Studies that compare repeat assessments of the same dogs have shown measurable differences between evaluators. The Norberg angle itself, introduced in the 1960s, was never formally standardised. This helps explain why discrepancies persist between readers and grading panels. In addition, the shape and orientation of the femoral head, femoral neck, and acetabulum vary between breeds. Applying a single set of radiographic criteria across all breeds can therefore lead to inconsistent or biased assessments (20, 21).

A specific Norberg angle value may indicate high-quality joint structure in one breed but lower-quality structure in another. This has led some researchers to argue for breed-specific percentile ranking rather than reliance on a single cross-breed threshold (22).

The presence of subjectivity does not make hip scoring unreliable. It means that each result should be interpreted as a measure of risk rather than as a definitive verdict. Despite its limitations, radiographic hip scoring remains the established standard across Europe and the only system that allows meaningful comparison between dogs. When used collectively and transparently, it provides the best available framework for monitoring trends and improving joint health at the population level.

This also helps explain why results can sometimes surprise owners and breeders. A dog bred from parents with solid hip scores may later be assessed elsewhere and receive a different grade. This does not necessarily mean that the original breeding decision was unsound. Hip scores reflect:

- how radiographs are taken,

- how specific features are weighted,

- how borderline cases are handled, and

- how results are reported within a given screening framework.

Small differences in positioning, interpretation, or reporting conventions can shift a result across a grading threshold. When a complex, continuous trait is reduced to a single category, these shifts are unavoidable. Reading hip scores as context-dependent risk indicators rather than fixed biological facts helps make sense of such discrepancies.

Myth 5: Hip scores are individual verdicts, not population tools

Hip scoring was designed to reveal patterns, not to label individual dogs.

Hip scoring is often treated as a private judgement about an individual dog, something relevant only to breeders and their immediate decisions. In reality, its greatest value lies at the population level. When enough dogs are tested and results are shared, individual variation gives way to meaningful trends. These data allow us to estimate genetic progress, identify risk factors, and evaluate whether breeding strategies are actually improving joint health over time.

This population perspective is essential because hip dysplasia is a complex, multifactorial trait. No single radiograph can reveal a dog’s full genetic contribution or predict outcomes with certainty. What matters is how scores are distributed across families, generations, and cohorts. When data are analysed collectively, patterns emerge that cannot be seen at the level of the individual dog.

Several countries already use hip score data in this way. In Finland, for example, estimated breeding values are calculated by combining an individual dog’s score with those of its relatives. This approach helps reduce the influence of environmental factors such as positioning, sedation, or radiographic technique and has been shown to be more effective than selection based solely on an individual phenotype (23, 24).

For smaller or developing breed populations, the limiting factor is often not the availability of screening tools, but the amount of usable data. When only the best results are recorded, the picture becomes distorted. This makes it difficult to assess whether current selection practices are truly effective or simply appear so on paper. A moderate score that is included in the dataset adds information. A score that is withheld removes it.

Transparency is therefore not about judging individual dogs. It is about making population-level decisions possible. Open data allow long-term trends to be monitored, breeding values to be calculated, and health policies to be evaluated honestly. Hip scoring systems are imperfect, but they remain the best tools available for tracking joint health at the population level. They work best when participation is broad and results are interpreted collectively rather than as isolated verdicts.

Myth 6: Radiographs reveal all musculoskeletal problems

What is measurable is often mistaken for what matters most.

When a dog shows lameness or discomfort, hip dysplasia is often the first diagnosis suggested. This happens partly because it is one of the few musculoskeletal conditions most people recognise. Dogs, however, can injure or strain many different structures, and most people have limited familiarity with the complexity of canine anatomy. Because hip dysplasia is both familiar and measurable, it often becomes the default explanation for a wide range of problems.

This focus on the one condition we can quantify reinforces the idea that radiographs tell the whole story. In reality, X-rays show only static bone structure. They do not capture fascia, muscle tone, or neuromuscular control (25). Clinical signs such as pain or lameness often do not correlate well with the degree of radiographic change in the joint (26, 27). Two dogs with identical hip scores may therefore differ dramatically in how well their structure supports long-term function.

Dogs with “A” or “Excellent” hips can still develop muscle strains or joint dysfunction due to muscular imbalance (28). Conversely, very tight hips can transfer stress to surrounding soft tissues, leading to pain that never appears on a radiograph. Problems may also arise from early injury, poor conditioning, or compensatory tension following slips or falls.

Whole-body structure plays a major role in how forces travel through the hindquarters. A well-angled pelvis and moderate rear angulation allow smooth and efficient load transfer through the hip joint. A flat or short croup alters pelvic tilt and changes how the femoral head sits in the socket during movement, increasing mechanical stress. At the other extreme, excessive angulation can promote instability and overuse of soft tissues. In moderate, functionally balanced breeds such as the Polish Hunting Spaniel, proportionate structure provides a degree of natural protection against abnormal joint loading.

Body proportions also matter. A study across multiple breeds found a strong association between increased body length relative to height and the prevalence of hip dysplasia. Dogs described as “slightly long” or “long” had average hip-dysplasia scores more than eight times higher than square-bodied dogs (29). This potentially suggests that maintaining moderate, functional proportions is one of the simplest ways to reduce joint strain.

In short, hind-end lameness is not synonymous with hip dysplasia. In practice, conditions affecting the hip, stifle, iliopsoas, or lumbosacral region can produce similar signs. Radiographs alone rarely identify the true source of pain without a thorough clinical examination.

Myth 7: All dogs should be evaluated with the same HD standards

Screening standards reflect the populations they were built for.

Hip dysplasia screening did not arise as a universal health initiative. It emerged in the 1950s from large-scale service-dog programmes in Sweden and Germany, where training represented a substantial economic investment and dogs that developed lameness after selection or training constituted costly failures (30, 31). The primary goal of early screening was therefore not to define ideal hips, but to reduce financial loss by excluding dogs at higher risk of future breakdown as early as possible. Radiographic assessment offered a practical, scalable way to make those decisions before significant resources were invested.

As these methods proved effective, they were adopted by kennel clubs and expanded into national breeding programmes. One of the most influential examples is the Swedish Kennel Club’s landmark study of more than 83,000 dogs from seven large or giant breeds, which demonstrated that systematic screening and selective breeding could reduce the prevalence of hip dysplasia over time (32). These results were important and remain widely cited. However, they were derived from populations that shared key structural characteristics, including greater body mass, longer backs, and pelvic configurations typical of large working breeds.

Much of the subsequent hip dysplasia research has continued to draw from similar populations. Medium-sized, moderate, and agile breeds are comparatively under-represented in large longitudinal datasets, creating an evidence gap when findings are extrapolated beyond the populations in which screening systems were originally validated.

Early researchers reasonably assumed that improving hip integrity in heavy, high-risk breeds would benefit all dogs. In practice, however, applying identical radiographic criteria across breeds with different morphology, biomechanics, and functional demands does not eliminate bias – it just relocates it. Standards calibrated within one structural context inevitably reflect that context, even when applied elsewhere.

For breeds such as the Polish Hunting Spaniel, which are built for agility rather than sustained high load, some degree of joint compliance may be both normal and functionally appropriate. Holding such dogs to standards developed around large, heavily muscled service breeds risks misclassification and, over time, unnecessary loss of genetic diversity.

Recognising the historical origins of hip dysplasia screening is not an argument for lowering expectations or excusing poor joint health. It is an argument for understanding how standards were shaped, where their strengths lie, and where caution is required when applying them beyond their original biological context.

Screening remains a valuable tool but like all tools, it works best when used with an awareness of how and why it was designed.

Myth 8: The same hip score means the same thing in every breed

The same label can arise from different anatomy and different risks.

Hip scores are often treated as interchangeable across breeds. A “C” is assumed to represent the same underlying problem, risk, and likely outcome whether it appears in a German Shepherd, a retriever, or a spaniel. In practice, this assumption does not hold.

The basic biological mechanisms that govern hip joint development and degeneration are broadly conserved across dogs. However, multiple studies show that the geometry, biomechanics, and load distribution of the canine hip joint vary systematically between breeds (34, 35, 47). These differences influence how radiographic features appear and how measures such as joint congruency, coverage, and apparent laxity should be interpreted.

Hip scores are aggregate outcomes that combine several radiographic observations into a single grade. The same final score can therefore be reached through different combinations of findings, even within one breed. Breeds also differ in body proportions, and how forces move through the body – because of this, the same hip score can be reached for different reasons in different breeds.

Direct, breed-to-breed comparisons of hip morphology are limited largely because such studies are difficult to perform at scale. Large datasets tend to prioritise statistical power over anatomical detail, while detailed imaging studies usually involve small numbers of dogs. This evidence gap does not mean that breeds are anatomically identical. It means that conclusions must be drawn from converging lines of evidence rather than from a single definitive study.

Population data provide an important part of that evidence. Large, relatively stiff breeds such as German Shepherd Dogs tend to cluster toward lower baseline joint laxity, while breeds such as Golden Retrievers and spaniel types are more likely to show greater joint compliance (38). These patterns reflect normal biological variation rather than disease. When identical grading thresholds are applied across such populations, flexible but functional joints may be more likely to fall into borderline categories even in the absence of pain, degeneration, or impaired performance.

Historical context also matters. Many hip dysplasia screening standards were developed using data from service-dog and working-dog populations in which certain large breeds were heavily represented. These standards were effective for reducing severe disease in those populations. At the same time, they shaped expectations of what “normal” hips should look like. Applying those expectations without adjustment to breeds with different structure and function can distort interpretation. The same hip grade can therefore arise from different underlying radiographic features. Because breeds differ in baseline joint compliance and morphology, identical scores do not necessarily reflect identical mechanisms or identical functional outcomes.

Hip scores remain valuable tools, but they are best understood as population-context indicators rather than universal biological constants.

Why canine hip anatomy cannot be treated as identical across breeds

The biological mechanisms of hip joint disease are broadly conserved across dogs. In contrast, evidence from morphometric and biomechanical studies shows that hip geometry and load distribution vary systematically between breeds. These differences have important implications for how radiographic findings should be interpreted.

Research examining hip joint morphology has demonstrated consistent breed-related variation in pelvic width and orientation, acetabular shape and depth, femoral head shape, femoral neck length, and neck–shaft angle. In several cases, this research was driven by practical needs such as improving the design and fit of hip prostheses. This confirms that the anatomical differences observed are large enough to matter clinically.

Clear examples come from small and medium breeds such as Dachshunds, Toy Poodles and Pembroke Welsh Corgi (49). These breeds show acetabular and femoral shapes that differ markedly from those seen in large working breeds. Because of this, commonly used radiographic measures such as femoral head coverage, apparent joint congruency, and neck–shaft angle do not behave in the same way across all breeds.

Biomechanical studies further show that hip morphology affects how forces are transmitted through the joint. Dogs with different hip configurations display different patterns of load distribution across the acetabulum, differences in subchondral bone mineralisation, and distinct stress distributions within the joint. These findings highlight that the hip functions as a biomechanical system rather than as a static arrangement of bones.

Importantly, this work explicitly recognises breed-dependent biomechanics, including differences in pelvic load transfer and force vectors acting on the acetabulum. Joint congruency and assessments of “normality” therefore cannot be interpreted meaningfully without considering biomechanics alongside radiographic appearance.

Why is there so little direct research on breed differences?

Direct, breed-to-breed comparisons of hip joint morphology and biomechanics are rare. This is not because breeds are assumed to be identical, but because such studies are difficult to design and execute. Large sample sizes are needed within each breed. Imaging methods must be standardised. Ethical constraints limit experimental manipulation. As a result, most large datasets combine breeds to gain statistical power, while detailed anatomical studies focus on small numbers of dogs for specific clinical or engineering purposes.

This type of research is also expensive and difficult to fund. Proper breed-comparative studies would require advanced imaging such as CT or MRI, standardised positioning and sedation protocols, specialist analysis of joint geometry and load distribution, and long-term follow-up to link structure with outcome. Each of these steps adds cost, and together they often exceed the scope of typical academic veterinary research budgets.

The work also falls into a funding gap. It is not commercially attractive, as it does not lead directly to a product. It is not clinically urgent, since funding bodies tend to prioritise acute disease and treatment. It is not well suited to breed-club funding, which usually focuses on prevalence reduction rather than anatomical detail. Human orthopaedic research also translates poorly, because dog breeds are uniquely diverse in size, shape, and selection history. As a result, there is no obvious stakeholder to fund large, systematic, breed-comparative studies of hip anatomy.

The absence of large comparative studies does not imply the absence of meaningful differences. Instead, evidence comes from multiple converging sources, including morphometric analyses, biomechanical studies, population-level laxity data, and basic principles of functional anatomy. Taken together, these lines of evidence indicate that hip structure and load behaviour vary systematically between breeds, even though the underlying biological mechanisms of joint development and degeneration are broadly conserved.

Myth 9: “Once an A hip, always an A hip”

A screening result describes a moment in time, not a lifetime outcome.

The belief that “once an A hip, always an A hip” turns a screening result into a lifetime guarantee. It suggests that hip dysplasia is decided early, resolved by screening, and no longer relevant once a dog has passed. This belief is not just inaccurate—it creates false certainty and encourages complacency.

Hip dysplasia develops during growth, which has led many people to assume that hip status is fixed once screening is completed. In reality, hip scores describe how the joint looks on the day the X-ray is taken. They do not lock the joint into a permanent state, and they do not eliminate future risk.

Hip screening does not measure the early developmental changes that predispose a dog to dysplasia. It evaluates bone shape, joint fit, and visible signs of change at a specific moment in time. These features reflect how the joint has responded to load and use up to that point, not how it will respond for the rest of the dog’s life.

Evidence shows that hip scores are influenced by age. In Labrador Retrievers, dogs scored at younger ages tended to receive better scores than the same dogs evaluated later, and ignoring age at scoring distorted interpretation of results (51. A hip classified as “A” at the standard screening age might not receive the same classification if assessed years later.

Long-term follow-up studies reinforce this point. In a lifetime study of Labrador Retrievers, many dogs that passed hip screening at the accepted age later showed clear evidence of osteoarthritis when examined at the end of life (52). Early radiographic normality reduced risk, but it did not reliably predict lifelong joint health.

The idea that hip status is permanent persists partly because dogs are rarely re-screened. Results are recorded once, then treated as settled facts unless a problem arises. Changes that occur gradually over time therefore remain unseen, reinforcing the illusion that scores never change. This myth matters because it shifts responsibility. If an “A” hip is treated as a permanent guarantee, management starts to feel optional. Conditioning, body weight, flooring, workload, and injury prevention are quietly downgraded in importance. In reality, these factors continue to shape joint health long after screening is complete.

An “A” hip means exactly one thing: the joint met the criteria for that grade on the day it was evaluated. It does not mean the joint is immune to change, and it does not mean future outcomes are irrelevant. Hip screening reduces risk, but it does not end the story. In working and athletic dogs, including service dogs, injury risk and long-term joint health are shaped by how the body is conditioned, loaded, and managed throughout life. Clinical guidance from service-dog populations emphasises that physical conditioning, weight control, and regular assessment reduce musculoskeletal injury and support long-term function. An “A” hip does not replace these responsibilities – it simply removes one risk factor from a much larger equation. Treating a good hip score as the end of the story ignores what ultimately protects joints over time: thoughtful management, appropriate workload, and ongoing care.

Treating an early score as a lifelong verdict replaces ongoing care with false reassurance. Hip dysplasia may start early, but hip health is negotiated over a lifetime.

Myth 10: Laxity is always a flaw

In hip dysplasia screening, joint tightness is often treated as a universal ideal, regardless of breed or function.

The limited range of dog breeds studied in hip dysplasia research has contributed to the widespread assumption that joint laxity is always a defect. In reality, a small degree of flexibility can serve an important biomechanical purpose. Connective tissues such as tendons and fascia act like natural springs. They stretch to absorb impact and then recoil to release energy. This mechanism reduces muscular effort and helps protect tissues from strain when a dog turns sharply, lands from a jump, or moves over uneven terrain (33).

Data from the PennHIP database show that normal joint looseness varies widely between breeds. Borzois and Greyhounds have average Distraction Index values around 0.2–0.25, while many spaniel breeds commonly fall in the 0.5–0.6 range. These differences reflect not defects, but distinct mechanical balances shaped by size, body type, and functional demands. Breeds selected for long, straight-line running tend to have tighter hip sockets and firmer connective tissues. Dogs bred for quick acceleration, crouching, and frequent changes of direction often show greater joint compliance.

All dogs rely on elastic tissues to store and return energy during movement, but how that elasticity functions depends on the dog’s build and purpose. In breeds such as the Greyhound, a deeper hip socket and firmer supporting tissues help stabilise the joint during powerful, linear motion. In spaniel-type dogs, slightly greater flexibility may allow a wider range of motion and smoother recovery when turning or working close to the ground. Greyhounds can be compared to racing bikes, optimised for speed and efficiency on smooth, predictable surfaces. Polish Hunting Spaniels are more like mountain bikes, built to handle uneven terrain, rapid turns, sudden stops, and short bursts of effort.

The Polish Hunting Spaniel works through dense cover using repeated stop-and-go movement and abrupt changes of direction. In this context, a degree of elasticity may help absorb impact and reduce soft-tissue strain. This principle is well recognised across species. Compliant tendons and ligaments act as shock absorbers and improve energy efficiency in agile animals (34).

Similar principles are well recognised in humans. Different sports favour different mechanical balances. Gymnasts and dancers often display a high degree of joint mobility, which allows large ranges of motion and efficient energy absorption. Weightlifters and power athletes, by contrast, typically benefit from stiffer joints and tighter connective tissues that favour force transmission and stability under load. Neither profile is inherently healthier than the other, and each is well suited to the demands placed on the body.

However, in both humans and dogs, above-average joint mobility requires strong, well-coordinated muscles to remain protective rather than predisposing to injury. Functional health therefore lies not in eliminating every trace of laxity, but in ensuring that connective tissues, muscles, and skeletal structure work together to meet the physical demands of the dog’s job.

A brief personal note: I speak about this not only as a breeder or researcher, but also from personal experience. I am hypermobile myself, something I did not discover until my forties. Because I was never particularly drawn to sport or strength training, I now experience the consequences of having above-average joint mobility without sufficient muscular support and have researched this topic in humans as well. That combined perspective has made the importance of strength, conditioning, and neuromuscular control very tangible to me, both in people and in dogs.

Conclusion

Hip scores offer the comfort of clarity, but that clarity is often mistaken for certainty.

A letter or number can look like a verdict, even though it represents a filtered snapshot shaped by assumptions about anatomy, age, breed, and population context. When those limits are ignored, risk indicators are treated as biological facts.

All of the myths explored here trace back to the same error: reducing a complex, time-dependent condition to a simple pass–fail outcome. Hip dysplasia is not binary, hip scores are not universal, and screening was never designed to deliver guarantees. Used without context, scores can narrow gene pools, penalise normal variation, and shift attention away from the factors that continue to shape joint health throughout life.

Screening works when it is understood for what it is: a population-level tool for reducing risk, not eliminating it. Hip scores are not verdicts about worth or fate, and they do not replace informed breeding decisions or lifelong responsibility for management and care. Hip health is built over time, through the interaction of structure, load, movement, and environment.

The original purpose of screening was to support sound, functional dogs through better-informed choices — and it only succeeds when we resist the temptation to treat simple answers as complete ones.

REFERENCES

1. Wilson, B.J., Nicholas, F.W., James, J.W., Wade, C.M., Raadsma, H.W., & Thomson, P.C. (2011). Estimated breeding values for canine hip dysplasia radiographic traits in a cohort of Australian German Shepherd Dogs. PLoS One, 6(10), e26470.

2. Breur, G. J., Lambrechts, N. E., & Todhunter, R. J. (2012). The genetics of canine orthopaedic traits. In The genetics of the dog (pp. 136-160). Wallingford UK: CABI.

3. Hou, Y., Wang, Y., Lu, X., Zhang, X., Zhao, Q., Todhunter, R. J., & Zhang, Z. (2013). Monitoring hip and elbow dysplasia achieved modest genetic improvement of 74 dog breeds over 40 years in USA. PloS one, 8(10).

4. Ginja, M. M. D., Silvestre, A. M., Gonzalo-Orden, J. M., & Ferreira, A. J. A. (2010). Diagnosis, genetic control and preventive management of canine hip dysplasia: a review. The Veterinary Journal, 184(3), 269–276.

5. Tomlinson, J. L., & Johnson, J. C. (2000). Quantification of measurement of femoral head coverage and Norberg angle within and among four breeds of dogs. American Journal of Veterinary Research, 61(12), 1492–1500.

6. Sallander, M. H., Hedhammar, Å., & Trogen, M. E. (2006). Diet, exercise, and weight as risk factors in hip dysplasia and elbow arthrosis in Labrador Retrievers. The Journal of Nutrition, 136(7), 2050S–2052S.

7. Swenson, L., Audell, L., & Hedhammar, Å. (1997). Prevalence and inheritance of and selection for hip dysplasia in seven breeds of dogs in Sweden and benefit:cost analysis of a screening and control program. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 210(2), 207–214.

8. Hedhammar, A. (2007). Canine hip dysplasia as influenced by genetic and environmental factors. EJCAP, 17(2), 141-3.

9. Feng, L. C., Philippine, A., Ball-Conley, E., & Byosiere, S.-E. (2025). Fleece-Lined Whelping Pools Associated with Reduced Incidence of Canine Hip Dysplasia in a Guide Dog Program. Animals, 15(2), 152.

10. Riser, W. H., & Shirer, J. F. (1967). Correlation between canine hip dysplasia and pelvic muscle mass: a study of 95 dogs.

11. Cardinet, G. H., Kass, P. H., Wallace, L. J., & Guffy, M. M. (1997). Association between pelvic muscle mass and canine hip dysplasia. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 210(10), 1466-1473.

12. Edge-Hughes, L. (2007). Hip and sacroiliac disease: selected disorders and their management with physical therapy. Clinical techniques in small animal practice, 22(4), 183-194.

13. Ginja, M. M. D., Silvestre, A. M., Colaço, J., Gonzalo-Orden, J. M., Melo-Pinto, P., Orden, M. A., … & Ferreira, A. J. (2009). Hip dysplasia in Estrela mountain dogs: prevalence and genetic trends 1991–2005. The Veterinary Journal, 182(2), 275-282.

14. Popovitch, C.A., Smith, G.K., Gregor, T.P. & Shofer, F.S. (1995). Comparison of Susceptibility for Hip-Dysplasia between Rottweilers and German-Shepherd Dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 206(5), 648-650.

15. Krontveit, R. I., Nødtvedt, A., Sævik, B. K., Ropstad, E., & Trangerud, C. (2012). Housing- and exercise-related risk factors associated with the development of hip dysplasia as determined by radiographic evaluation in a prospective cohort of Newfoundlands, Labrador Retrievers, Leonbergers, and Irish Wolfhounds in Norway. American Journal of Veterinary Research, 73(6), 838–846.

16 Mikkola, L. (2020). It’s complex: studies on the genetics of canine hip dysplasia. Helsingin Yliopisto.

17. Culp, W. T. N., Kapatkin, A. S., Gregor, T. P., Powers, M. Y., McKelvie, P. J., & Smith, G. K. (2006). Evaluation of the Norberg Angle Threshold: A Comparison of Norberg Angle and Distraction Index as Measures of Coxofemoral Degenerative Joint Disease Susceptibility in Seven Breeds of Dogs. Veterinary Surgery, 35(5), 453–459.

18. Carneiro, R. K., da Cruz, I. C., Lima, B., et al. (2024). Comparison of the distraction index and Norberg angle with radiographic grading of canine hip dysplasia. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound, 65(2), 107–113.

19. Smith, G. K., Gregor, T. P., Rhodes, W. H., & Biery, D. N. (1993). Coxofemoral joint laxity from distraction radiography and its contemporaneous and prospective correlation with laxity, subjective score, and evidence of degenerative joint disease from conventional hip-extended radiography in dogs. AmericanJjournal of Veterinary Research, 54(7), 1021-1042.

20. Tomlinson, J., Fox, D., Cook, J. L., & Keller, G. G. (2007). Measurement of femoral angles in four dog breeds. Veterinary surgery, 36(6), 593-598.

21. Wigger, A., Tellhelm, B., Kramer, M., & Rudorf, H. (2008). Influence of femoral head and neck conformation on hip dysplasia in the German Shepherd dog. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound, 49(3), 243–248.

22. Kacková, G., Horňák, S., Figurová, M., Vargová, N., & Tauberová, V. (2025). Morphometric evaluation of the hip joint in dogs. Folia Veterinaria, 69(1), 1-8

23. Malm, S. (2010). Breeding for improved hip and elbow health in Swedish dogs (No. 2010: 79). PhD thesis.

24. Malm, S., Sørensen, A. C., Fikse, W. F., & Strandberg, E. (2013). Efficient selection against categorically scored hip dysplasia in dogs is possible using best linear unbiased prediction and optimum contribution selection: A simulation study. Journal of Animal Breeding and Genetics, 130(2).

25. Tomlinson, J. L., & Johnson, J. C. (2000). Quantification of measurement of femoral head coverage and Norberg angle within and among four breeds of dogs. American Journal of Veterinary Research, 61(12), 1492–1500.

26. Ginja, M. M. D., Silvestre, A. M., Gonzalo-Orden, J. M., & Ferreira, A. J. A. (2010). Diagnosis, genetic control and preventive management of canine hip dysplasia: a review. The Veterinary Journal, 184(3), 269–276

27. Fries, C. L., & Remedios, A. M. (1995). The pathogenesis and diagnosis of canine hip dysplasia: a review. The Canadian Veterinary Journal, 36(8), 494.

28. Zink, C., & Van Dyke, J. B. (2018). Canine Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation.

29. Roberts, T., & McGreevy, P. D. (2010). Selection for breed-specific long-bodied phenotypes is associated with increased expression of canine hip dysplasia. The Veterinary Journal, 183(3), 266-272.

30. Henricson, B., & Olsson, S.-E. (1959). Hereditary acetabular dysplasia in German Shepherd dogs. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 135, 207–210

31. Olsson, S. E. (1961). Roentgen examination of the hip joints of German Shepherd Dogs. Adv Small Anim Pract, 3, 117-120.

32. Swenson, L., Audell, L., & Hedhammar, Å. (1997). Prevalence and inheritance of and selection for hip dysplasia in seven breeds of dogs in Sweden and benefit:cost analysis of a screening and control program. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 210(2), 207–214.

33. Konow, N., & Roberts, T. J. (2015). The series elastic shock absorber: tendon elasticity modulates energy dissipation by muscle during burst deceleration. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 282(1804), 20142800.

34. Bryce, C. M., Wilmers, C. C., & Williams, T. M. (2017). Energetics and evasion dynamics of large predators and prey: pumas vs. hounds. PeerJ, 5, e3701.

35. Küchenmeister, K. (2007). Computed tomography osteoabsorptiometry of the canine hip joint (Doctoral dissertation, University of Munich). Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich Repository.

36. Bäcker, M. (2010). Geometric configuration of the hip joint in small-breed dogs (Doctoral dissertation, University of Zurich). University of Zurich Repository.

37. Verhoeven, G., Fortrie, R., Van Ryssen, B., & Coopman, F. (2012). Worldwide screening for canine hip dysplasia: where are we now?. Veterinary surgery : VS, 41(1), 10–19.

38. Bowen J, Fatjó J, Serpell JA, Bulbena-Cabré A, Leighton E, Bulbena A. First evidence for an association between joint hypermobility and excitability in a non-human species, the domestic dog. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):8629.

39. Ginja, M., Gonzalo-Orden, J. M., & Ferreira, A. (2021). Editorial: Canine Hip and Elbow Dysplasia Improvement Programs Around the World: Success or Failure?. Frontiers in veterinary science, 8,

40. Hedhammar Å. (2020). Swedish Experiences From 60 Years of Screening and Breeding Programs for Hip Dysplasia-Research, Success, and Challenges. Frontiers in veterinary science, 7, 228.

41. Lewis, T. W., Blott, S. C., & Woolliams, J. A. (2013). Comparative analyses of genetic trends and prospects for selection against hip and elbow dysplasia in 15 UK dog breeds. BMC genetics, 14, 16.

42. Leppänen, M., & Saloniemi, H. (1999). Controlling canine hip dysplasia in Finland. Preventive veterinary medicine, 42(2), 121–131.

43. Soo, M., & Worth, A. (2015). Canine hip dysplasia: phenotypic scoring and the role of estimated breeding value analysis. New Zealand veterinary journal, 63(2), 69–78.

44. Vanden Berg-Foels, W. S., Todhunter, R. J., Schwager, S. J., & Reeves, A. P. (2006). Effect of early postnatal body weight on femoral head ossification onset and hip osteoarthritis in a canine model of developmental dysplasia of the hip. Pediatric research, 60(5), 549-554.

45. Leighton, E. A., Holle, D., Biery, D. N., Gregor, T. P., McDonald-Lynch, M. B., Wallace, M. L., Reagan, J. K., & Smith, G. K. (2019). Genetic improvement of hip-extended scores in 3 breeds of guide dogs using estimated breeding values: Notable progress but more improvement is needed. PloS one, 14(2).

46. Wang, S., Laloë, D., Missant, F. M., Malm, S., Lewis, T., Verrier, E., … & Leroy, G. (2018). Breeding policies and management of pedigree dogs in 15 national kennel clubs. The Veterinary Journal, 234, 130-135.

47. Franklin, S. P., Franklin, A. L., Wilson, H., Schultz, L., Sonny Bal, B., & Cook, J. L. (2012). The relationship of the canine femoral head to the femoral neck: an anatomic study with relevance for hip arthroplasty implant design and implantation. Veterinary surgery : VS, 41(1), 86–93.

48. Ogden, D. M., Scrivani, P. V., Dykes, N., Lust, G., Friedenberg, S. G., & Todhunter, R. J. (2012). The S-measurement in the diagnosis of canine hip dysplasia. Veterinary surgery : VS, 41(1), 78–85.

49. Karbe, G. T., Biery, D. N., Gregor, T. P., Giger, U., & Smith, G. K. (2012). Radiographic hip joint phenotype of the Pembroke Welsh Corgi. Veterinary surgery : VS, 41(1), 34–41.

50. Smith, G. K., Lawler, D. F., Biery, D. N., Powers, M. Y., Shofer, F., Gregor, T. P., Karbe, G. T., McDonald-Lynch, M. B., Evans, R. H., & Kealy, R. D. (2012). Chronology of hip dysplasia development in a cohort of 48 Labrador retrievers followed for life. Veterinary surgery : VS, 41(1), 20–33.

51. Wood, J. L. N., & Lakhani, K. H. (2003). Hip dysplasia in Labrador retrievers: The effects of age at scoring. Veterinary Record, 152(2), 37–40.

52. Smith, G. K., et al. (2012). Chronology of hip dysplasia development in a cohort of 48 Labrador Retrievers followed for life. Veterinary Surgery, 41(1), 20–33.

Excellent article, comprehensive and precise, full of information and food for thought.

LikeLike