We ask a great deal of dogs in modern life. We expect them to adapt to environments they did not evolve for and to tolerate situations that would be sensible to approach with caution. If we are going to ask that much, it follows that we have a responsibility to stack the odds in their favour. This article is about one place where that leverage exists: early life, before most owners are ever involved.

Every year, fireworks trigger the same conversations about dogs. Videos circulate of terrified animals, advice is shared about management and training, and people swap stories about dogs who cope and dogs who do not. The focus is usually on what owners can do now. What is discussed far less is what happened before those dogs ever came home.

Fireworks are a useful example, but they are not the point. Sound sensitivity is just one visible stress test of something broader: how a dog’s early life shapes its baseline for coping with the world. Noise, novelty, handling, movement, frustration, and recovery all draw on the same underlying systems. Early life is when those systems are first being put together.

By the time a puppy comes home, that process is already well underway. Puppies are not blank slates at eight weeks, and owners cannot change what happened before then. This is not a story about effort or intention. It is about what can only happen early, and what has to work with whatever foundation is already there.

The difficulty is that this part of development is largely invisible. Most people have no reason to learn about it, because getting a dog is a one-off event. Buyers do not know what to ask about, and breeders are rarely pressed to show work that happens quietly, long before problems appear. As a result, outcomes depend heavily on chance, unevenly distributed.

If you would prefer to listen to this in a podcast version, you can download it here in ENGLISH, GERMAN or POLISH.

Why early life carries so much weight

In the first weeks of a puppy’s life, the brain and body are changing quickly. Hearing becomes functional, sensory input grows clearer, and the systems that regulate arousal and recovery begin learning how to work together. This is not just a period when puppies are picking things up; it is a period when the nervous system is being organised around the conditions it encounters.

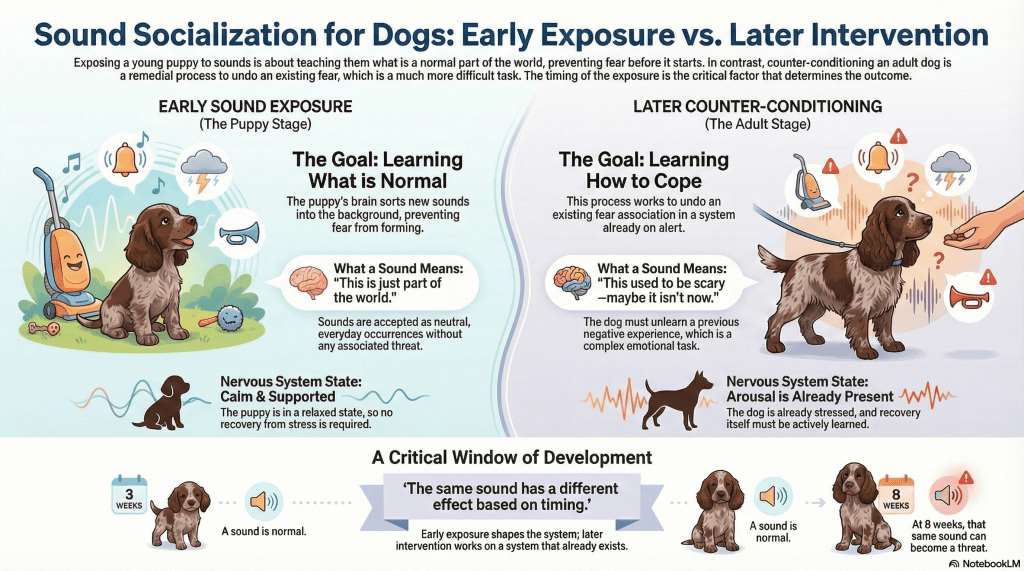

At this stage, experience does more than add information. It helps establish basic response patterns. The brain is learning what kinds of changes belong to ordinary life and which ones require heightened alertness. It is also learning how long a response should last—whether arousal resolves quickly, or lingers.

Context matters enormously here. Sounds introduced while puppies are fed, warm, and physically relaxed are processed very differently from the same sounds introduced under strain. When puppies hear noise after eating, while half asleep and curled together in a loose, contented pile, their nervous systems are already in a regulated state. Nothing is being asked of them. There is no need to cope, respond, or recover. Sound variation simply becomes part of the background of a safe world.

This matters because early on, the brain is not primarily learning what sounds mean. It is sorting how much they should count. When sounds occur in the middle of safety (social contact, full bellies, heavy bodies) they are less likely to be linked to urgency or prolonged arousal. Recovery happens automatically, because there was no disruption to begin with.

Neuroscience describes this as a period when the circuits involved in sensing the world, regulating emotion, and returning to baseline are especially open to being shaped by experience. These systems are developing together, not separately. How tightly sound is linked to emotional activation, how easily arousal rises, and how quickly it settles all begin to take shape during this early window.

By the time a puppy goes to a new home, much of this organisation has already happened. The brain remains capable of learning throughout life, but it is no longer in the same phase of rapid setup. Later experience can change responses but it works within patterns that are already in place.

This is why early experience has an influence that later work cannot simply recreate. It is not because the brain stops changing, or because later training is ineffective. It is because the particular conditions that exist early on when sound, safety, and regulation are being organised together do not return later.

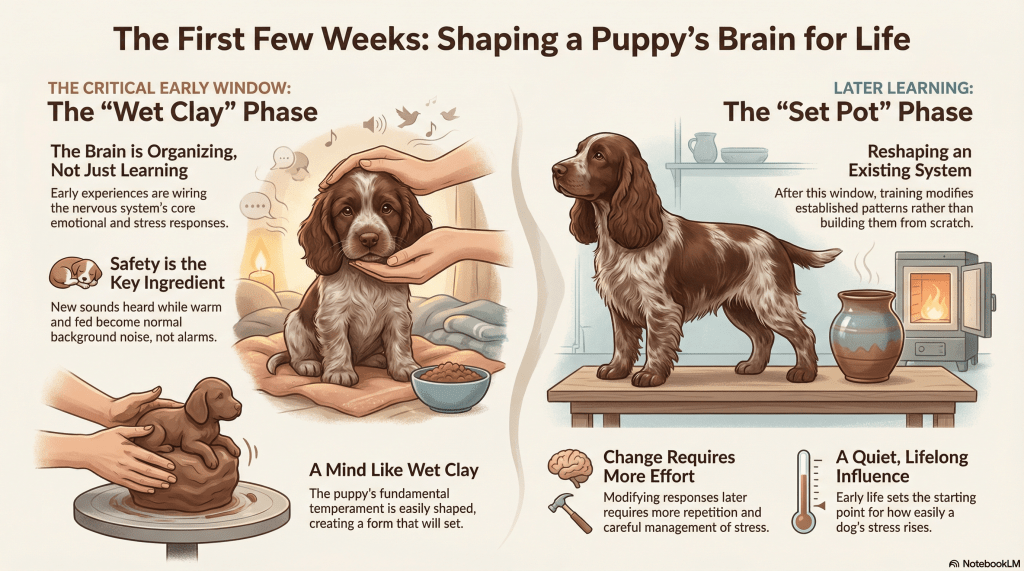

To understand a dog’s early development, one might think of their mind as soft clay on a potter’s wheel: in the first few weeks, the clay is very wet and easily shaped by every touch; as the socialization window closes, the clay begins to set, and while it can still be carved or polished later, the fundamental form and “cracks” created in those early moments become a permanent part of the finished vessel.

After that period, change is still possible, but it usually requires more repetition and more careful management. Progress can be real, but it may be more vulnerable when stress accumulates. That difference is not about effort or skill. It reflects the fact that later work is reshaping an existing system rather than helping to organise it at the outset.

Early life does not dictate a dog’s future, but it does influence the starting point. Over time, small differences in how easily stress rises, how long it lingers, and how readily it spreads can accumulate. That is how early experience comes to matter—not as destiny, but as a quiet influence on how much work ordinary life requires.

Even if you are not deeply interested in puppy development, the next section lays out the detailed, specific reasons for why it is not possible to fully compensate for the sound desensitisation in later life.

Week 3 is a developmental turning point

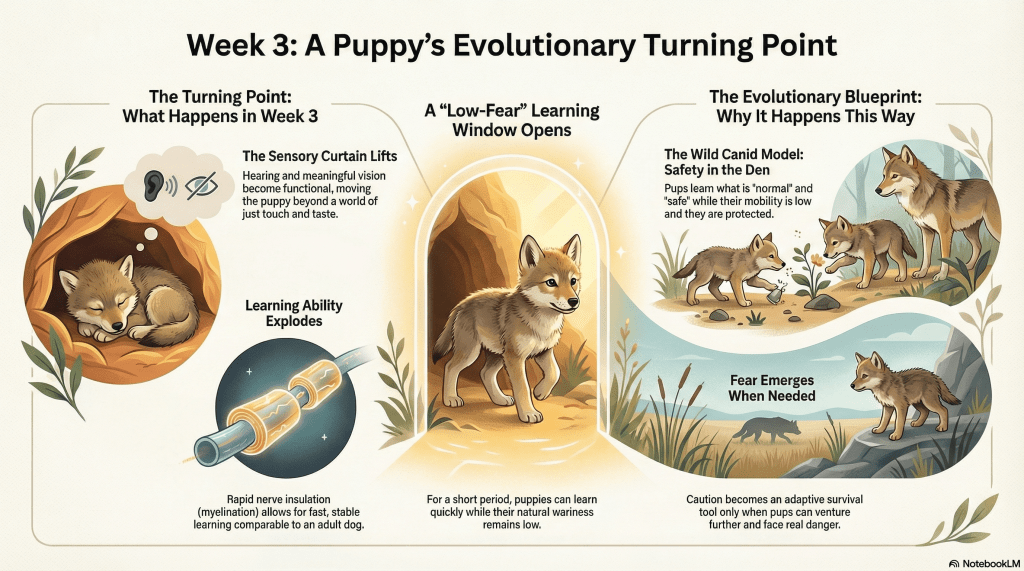

Week three marks one of the most dramatic transitions in a puppy’s development. Behavioural scientists often describe it as a behavioural metamorphosis: the point at which the puppy moves from a protected neonatal state into an organism that can meaningfully perceive, learn about, and respond to its environment. It represents the end of the Transition Period and the threshold of the Socialisation Period.

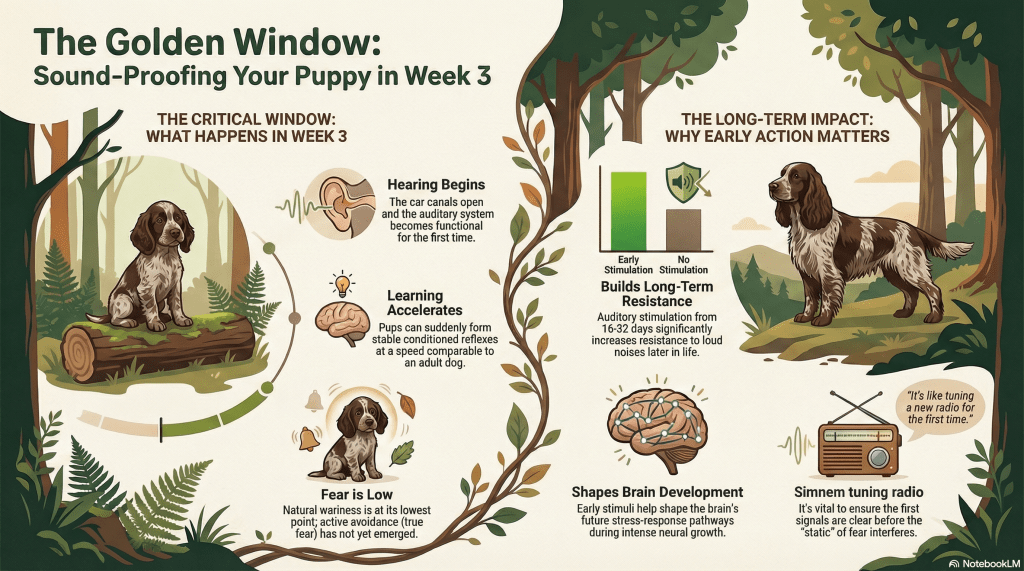

During the first two weeks of life, puppies inhabit a largely tactile world. Vision and hearing are not yet functional, and interaction with the environment is extremely limited. By the third week, this changes rapidly. As the ear canals begin to open (typically from around two weeks of age), auditory input gradually starts reaching the brain. Sensitivity and behavioural relevance develop over the following days, with clear startle responses to sudden sounds becoming more reliably observable toward the end of the third week. Vision follows a similar pattern: although the eyes open earlier, visual input only becomes neurologically meaningful as the underlying processing systems mature during this period so that puppies can process visual information rather than merely receive light.

By the end of week three, the sensory systems are largely functional, making this the first time a puppy can genuinely perceive its surroundings beyond touch and taste. This shift is often described as the lifting of a sensory curtain: the puppy’s world suddenly expands.

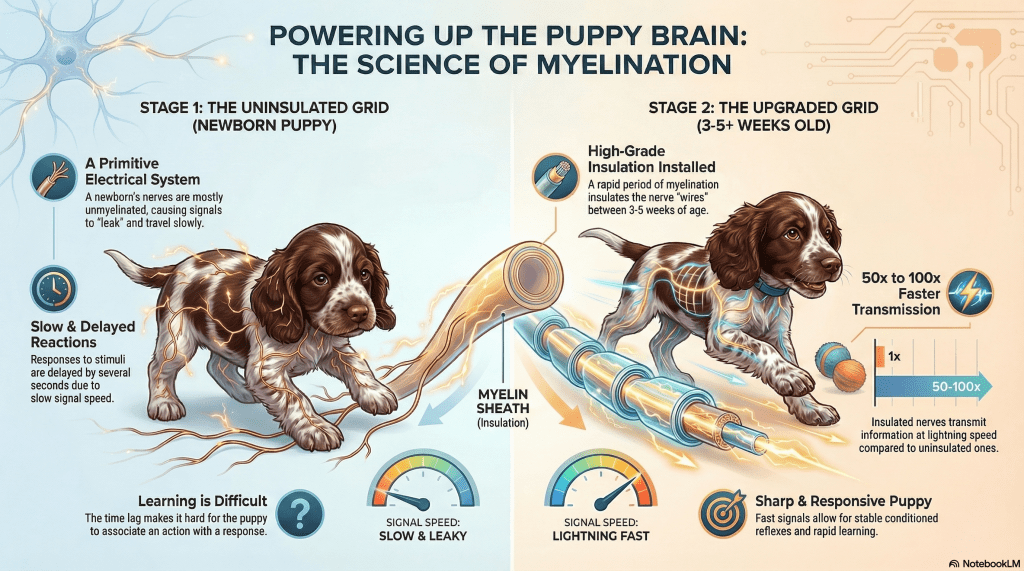

Earlier in life, learning is constrained by the immaturity of the nervous system. Newborn puppies have very little myelination—the insulating sheath around nerve fibres that enables fast signal transmission. As a result, responses to stimuli are slow, associations are difficult to form, and cause-and-effect learning is unreliable. Between 3-5 weeks, myelination accelerates sharply: as nerve fibres become insulated, signal transmission speeds increase dramatically, allowing puppies to form stable conditioned reflexes, associate events with consequences quickly, and learn at a speed comparable to an adult dog. This neurological shift underpins the puppy’s sudden capacity to make lasting associations with its environment.

Technical note on timing and sensory development

Ear canal opening in puppies typically begins around 14–16 days of age, with auditory input reaching the brain in a gradual and uneven way rather than at a single threshold. Behavioural startle responses to sudden sounds often become more clearly observable toward the end of the third week (approximately days 18–21), but this reflects increasing sensory salience and motor integration rather than the first moment of auditory function.

Vision follows a similar pattern. Although the eyes usually open earlier (around days 12–14), visual processing continues to mature over subsequent days as cortical circuits develop. In both cases, sensory access precedes meaningful processing, and meaningful processing precedes stable behavioural responses.

For this reason, developmental work is best understood as shaping how sensory input is processed during a sensitive period, not as reacting to a single developmental milestone.

Why this biologically protected low-fear window exists

Although puppies become sensitive to sound during week three, active avoidance of novelty (true fear) typically does not emerge until later (often around Week 5) and does not peak until closer to 8 weeks. This creates a short developmental window in which the auditory system is functional, learning is rapid, but wariness remains low. It reflects a tightly coordinated evolutionary solution to the problem of early learning under physical constraint.

In wild canids, young pups must begin to explore their immediate surroundings, interact with littermates, and acquire basic motor and social skills long before they are capable of effective avoidance or escape. At this stage, their physical range is extremely limited. They cannot travel far from the den, and they remain under close maternal supervision. This sharply reduces the likelihood of encountering genuinely novel or dangerous threats. If strong fear responses were present during this phase, exploration would be suppressed, learning would stall, and survival would be compromised. A pup that is too cautious early on does not become safer; it may not survive at all.

Crucially, this low-fear window also serves a second function: it is when the young animal learns which features of its environment are normal and safe. Sounds, movements, and sensory variation that occur while the pup is warm, fed, and protected within the den are, by definition, part of the background of a secure world. Treating those stimuli as dangerous would be maladaptive. The low-fear state allows the nervous system to classify environmental input, including sound, as ordinary rather than threatening, before avoidance systems come online.

The later emergence of a fear period is equally necessary. It coincides with a sharp increase in physical competence and range. As pups become capable of venturing further from the den, and maternal supervision necessarily loosens, heightened caution becomes adaptive. Fear now serves its protective function, guiding avoidance when the risk of genuine danger is real. Taken together, these phases reflect a coordinated developmental sequence. Low fear supports early exploration and environmental sorting when risk is low and mobility is constrained; later fear supports survival once independence and exposure increase.

Taken together, these phases reflect a coordinated developmental sequence. Low fear supports early exploration and environmental sorting when risk is low and mobility is constrained; later fear supports survival once independence and exposure increase. This is why sensory, motor, cognitive, and emotional changes converge at this stage: they are components of a single system calibrated to changing ecological risk.

This is why dismissing early sound exposure based on anecdote is misleading. Saying “the breeder did it and it didn’t work” ignores the fact that timing is the intervention. Sounds introduced during the low-fear window and sounds introduced a few weeks later are not the same experience to the puppy, even if the recordings are identical. Without knowing when and how it was done, the conclusion tells us very little.

When do you stop early sound exposure?

Early sound exposure is time-limited by design. Its purpose is calibration, not training, and once calibration has happened, continuing adds no benefit. In plain terms, you stop when hearing is clearly online and sound is no longer treated as salient. Practically, that usually looks like this:

- Start when puppies show the first signs of hearing (often around day 14–15, with individual variation).

- Use brief, low-pressure exposure (minutes, not sessions).

- Continue for around 5–7 days.

- Stop while responses remain neutral and recovery is immediate.

The key principle is: Stop while it is still calibration, not learning.

Signs the window has done its work include: brief orienting followed by disengagement, rapid return to baseline, no anticipation, tracking, or escalation.

Once puppies begin to consistently notice, orient toward, or expect sounds, the nervous system has moved past calibration and into learning. At that point, continuing early sound exposure no longer serves its original purpose. More exposure does not deepen resilience and can shift the process into habituation or training, which belongs later and in a different context.

This is why more is not better, and why early sound exposure is deliberately short and contained. The goal is not to eliminate startle or prove tolerance, but to help set a baseline where sound is sorted appropriately and recovery is easy.

Why safety matters in early sound exposure

Early sound exposure is therefore not as simple as “playing noises” and assuming the job is done. Under some conditions, it can even have the opposite effect. Research across neuroscience, developmental biology, and animal behaviour shows that early sensory experience is shaped not just by what is encountered, but by the internal state of the young animal at the time.

Across species, early development includes periods when the brain is especially open to being shaped by experience. During these windows, sensory circuits, stress regulation, and recovery systems are still being organised. Crucially, how this organisation unfolds depends on whether stimulation occurs in a calm, socially buffered state or under strain.

Studies in mammals and birds show a consistent pattern: when stimuli are experienced during low arousal (such as during feeding, rest, or close social contact) the nervous system is more likely to treat that variation as background information. Alarm thresholds remain higher, and recovery after disruption is faster. The same stimuli experienced during stress, isolation, or heightened arousal are more likely to be encoded as significant and to trigger lasting sensitivity.

This effect is closely tied to what researchers call social buffering: physical contact with the mother and littermates reliably reduces stress-hormone activity in young animals and shapes how the stress-response system develops. These effects are reflect measurable differences in how arousal and recovery circuits mature. Human infant research points in the same direction. Sensory input that occurs during calm, regulated states—such as feeding or skin-to-skin contact—is processed differently from identical input during distress. This is one reason neonatal care environments prioritise pairing stimulation with regulation rather than exposing infants to isolated or overwhelming sensory input.

Taken together, this body of evidence supports a simple conclusion. Early sound exposure works not because puppies are trained to tolerate noise, but because sound variation is encountered while the nervous system is already in a state of safety. In that context, sound is organised as part of ordinary life rather than as a signal that demands heightened alertness.

Why counter-conditioning later is different

When people talk about helping a dog cope with fireworks, the advice is often familiar. Play recordings of the sounds at low volume. Pair them with food or play. Gradually increase the intensity over time. Many owners recognise this approach, and some have tried it. This kind of work is usually described as desensitisation or counter-conditioning. It can be effective, and for some dogs it makes a real difference, but it is important to be clear about what it is and what it is not.

By the time a dog needs this kind of help, sound already carries emotional weight. The system is no longer being organised; it is being worked on. Counter-conditioning aims to change what a sound predicts by pairing it with safety, distance, or reward. That is a different operation from early shaping, and it comes with different limits and risks.

One of those risks is timing. Many puppies go to new homes between seven and nine weeks of age. This period can coincide with heightened sensitivity to novelty, increased caution, and a greater tendency for experiences (especially aversive ones) to leave a lasting mark. Individual variation is substantial: breed differences in developmental timing, sensory sensitivity, and juvenile behaviour are well documented, and factors such as sex, rearing conditions, maternal care, and early stress all influence how this phase unfolds.

What the evidence supports is not the idea that puppies are simply “afraid”, but that experiences during this time can carry more weight. Novel events may register as more salient, recovery may be slower, and learning (both positive and negative) can be stronger and more persistent than at other points in development.

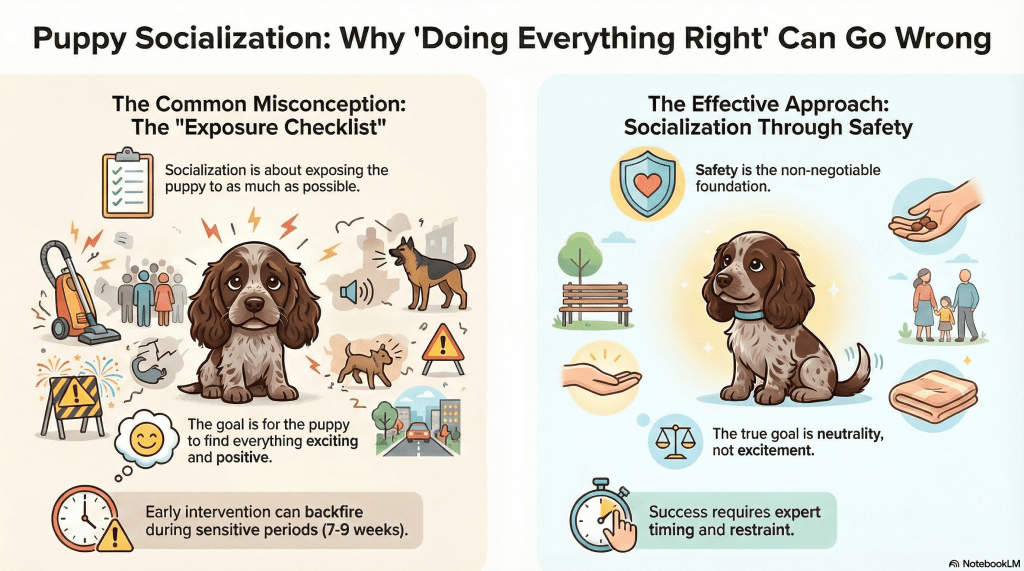

This matters because many eager, conscientious new owners quite reasonably try to “get started early” with what they have been told socialisation should look like. Sounds, people, places, and experiences are introduced promptly, often with care and good intentions. When difficulties like noise sensitivity appear later, it can feel deeply confusing because they did what they believed they were supposed to do.

Part of the problem is that much widely shared puppy advice is incomplete. Socialisation is often explained as exposure—make sure the puppy encounters things early—without enough attention to how those encounters are processed. Two elements are frequently missing:

- The goal of early exposure is not that puppies find everything positive or exciting. It is that most everyday variation registers as neutral.

- More importantly, exposure only does its intended work when the puppy feels safe. Safety is not a bonus; it is the condition that determines how experience is organised. Without it, the same exposure can increase sensitivity rather than reduce it.

During sensitive phases, well-intentioned sound work can therefore backfire. Exposure that might have been neutral or helpful at another time can increase vigilance or reactivity, especially when layered on top of the stresses of separation, travel, and a completely new environment. Recognising when this is happening requires careful observation of changes in posture, breathing, orientation, recovery speed and knowing when to pause or stop. That level of judgement is difficult even for people with extensive experience, so it is not something most new owners can reasonably be expected to do well while also learning to live with a puppy for the first time.

When I raised my first litter, I was acutely aware of how much responsibility that involved. Any mistake would not be mine alone; it would shape someone else’s life with their dog. For that reason, I worked with an experienced behaviourist to guide decisions during sensitive developmental periods. That support was not about following a checklist, but about timing, interpretation, and restraint. Most people never hear that this level of skill is involved, let alone that they might need help with it.

This is why so many owners believe they did what they were “supposed” to do and still end up with a dog who struggles. From the outside, it can look as though something was missed. In reality, they were attempting a form of intervention that is technically demanding and developmentally constrained, at a time when the margin for error is small.

Counter-conditioning remains valuable work as it can reduce fear and widen a dog’s life, but it is not a substitute for early shaping, and it is not a simple fallback when early opportunities have passed. Understanding that difference helps explain why later progress can be slow, fragile, or uneven and why this is not a reflection of insufficient effort or care.

If early experience matters so much, why do some dogs do fine without it?

Some dogs do fine because dogs differ: temperament, sensitivity, and recovery vary widely – within and between breeds. A robust dog can absorb a lot of imperfect early experience and still end up coping well. This fact is sometimes considered as an argument against doing the early work even though it is the opposite. Variation is exactly why early conditions matter: good early foundations protect the less robust dogs, not the ones who would have been fine anyway.

We do not refuse to improve schools because some children would have done well regardless. We improve early support to reduce avoidable difficulty across a population. Early puppy development works the same way: not guarantees, but better odds.

Early experience works the same way. While it does not guarantee a particular outcome, it changes the odds: fewer dogs end up overwhelmed, more dogs recover quickly, and owners spend less of the dog’s life managing fragility that was preventable.

N.B. Dogs are often used in research as comparative models to study learning, social cognition, and development relevant to humans (for example). Pointing to parallels in early development is therefore not an attempt to anthropomorphise dogs, but to acknowledge that some principles of how experience shapes behaviour are shared across species.

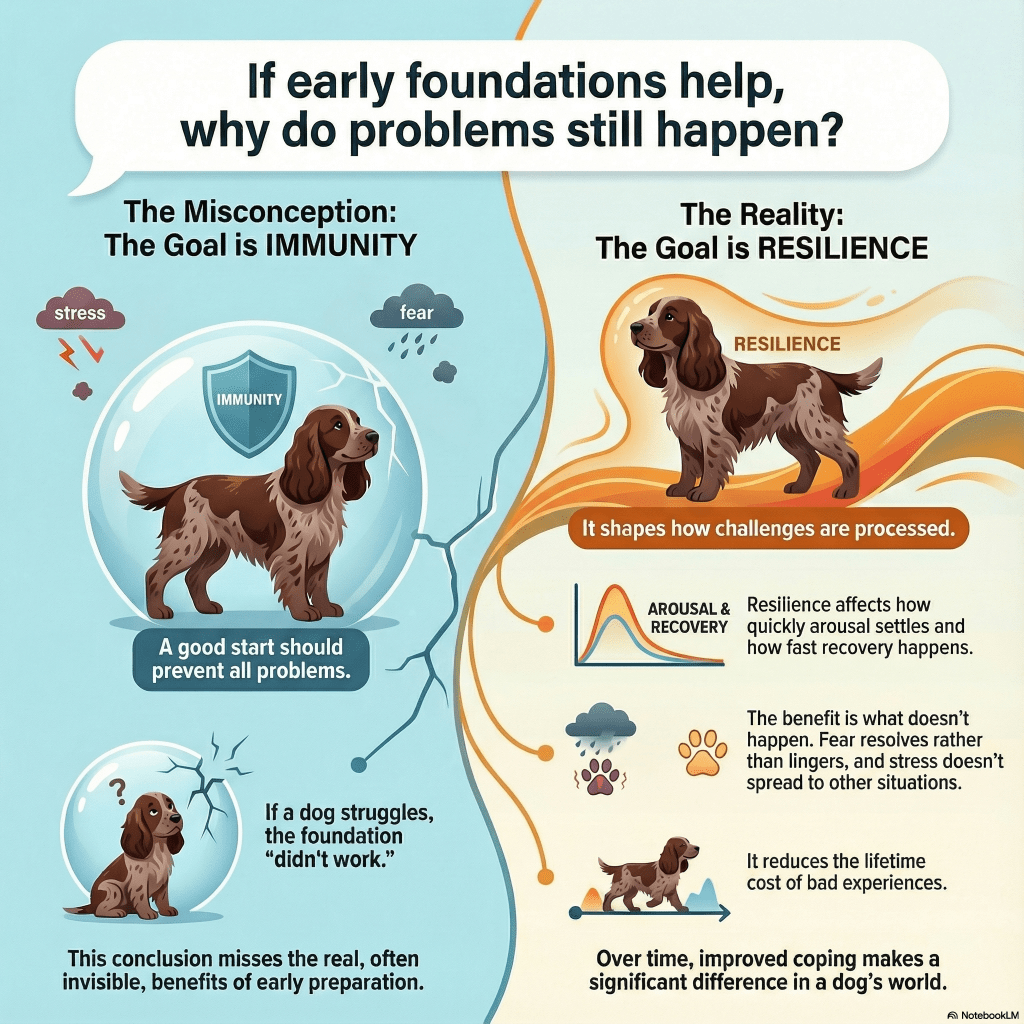

If early foundations help, why do problems still happen?

Because early foundations are not about preventing difficulty – they are about shaping how difficulty is handled. This is already familiar in human development. We generally agree that giving children a safe, supportive early start is important, even though it does not prevent later stress, adversity, or trauma. No one expects a good childhood to guarantee an easy life. The point is that early security changes how challenges are processed, how quickly recovery happens, and how much difficulty spills over into other areas.

The same logic applies here. Dogs with careful early preparation can still be startled by fireworks, frightened by unexpected events, or exposed to stressors beyond anyone’s control. A good start does not eliminate risk, and it does not promise smooth sailing. What early experience influences is what happens after something difficult occurs. It affects how quickly arousal settles, how likely stress is to spread to other situations, and how much strain accumulates over time. In other words, it shapes recovery, containment, and resilience – not immunity.

This distinction matters because it explains a common misunderstanding: when a dog with a good early foundation still struggles at some point, it can look as though the early work “didn’t work”. In reality, the benefit may be visible in what does not happen: the fear that resolves rather than lingers, the stress that stays local rather than generalising, the event that passes without quietly shrinking the dog’s world. When noise fears first appear later in life, this is often associated with underlying pain, particularly musculoskeletal discomfort, rather than with early developmental factors.

In short, early foundations reduce the cost of bad experiences even though they do not make them impossible and over a lifetime, that difference is matters.

Why do noise fears often appear around one year of age?

The first year of life carries disproportionate weight, not because dogs should be shielded indefinitely, but because biological vulnerability, experience, and maturation intersect most strongly during this period. When problems emerge later, they can feel sudden, but they are often the visible outcome of processes that have been unfolding quietly for months.

Research consistently finds that the median age of onset for firework fears is around one year, with a large proportion of affected dogs showing signs before their first birthday. This can be surprising to owners, especially when a puppy appeared to cope well earlier on. The reason lies in how development unfolds over time.

Manifestation versus development: Noise sensitivity does not suddenly begin at one year of age. Puppies can show startle responses to sound from very early in life, sometimes as early as a few weeks old. What often changes around the one-year mark is not the presence of sensitivity, but its manifestation. As dogs mature, early vulnerabilities are more likely to consolidate into stable, recognisable fear patterns rather than remaining brief or easily resolved reactions.

Adolescence and social maturity: The period between roughly six and fourteen months is one of rapid change. Dogs move through puberty and adolescence, with hormonal shifts and neurological reorganisation affecting how novelty, arousal, and threat are processed. In many breeds, this transition continues toward social maturity, which is reached at around twenty months, though timing varies substantially between individuals and breeds. Behavioural traits related to fear and reactivity often become clearer during this phase.

Cumulative exposure and sensitisation: As a dog moves through its first year, the likelihood of encountering loud, unpredictable noises inevitably increases. While some exposure leads to habituation, repeated startling experiences can also result in sensitisation, where responses intensify rather than diminish. Once sensitisation has begun, fear can generalise, spreading from one type of noise (such as fireworks) to others (like slamming doors or sudden movements), even without a single dramatic incident.

Genetic predisposition and individual timing: Consistent breed-group differences in noise sensitivity suggest a meaningful genetic contribution. Some dogs are biologically more vulnerable, and some breeds reach the point where they begin avoiding novelty earlier than others. This means that the timing of when a fear becomes obvious is not uniform. Two dogs with similar experiences may diverge sharply in how and when sensitivity emerges.

Why this catches owners off guard: This developmental convergence often overlaps with the steepest part of the new owner learning curve. Early opportunities for prevention are largely invisible in hindsight, while clearer signs of fear tend to appear later, just as the dog’s responses are becoming more stable. Many owners only realise something is wrong once the window for easy influence has begun to narrow.

What this implies for breeders and buyers

Fireworks are a yearly reminder that many of the problems we notice in adult dogs have a long lead time. When a dog panics on New Year’s Eve, the obvious question is what the owner can do tonight. The quieter, harder question is what happened weeks earlier—before that dog ever came home—when its baseline for processing novelty and disruption was still being set.

That is why early developmental work is not a nice extra. It is one of the few aspects of a dog’s future behaviour that is both time-limited and high-leverage. If it matters, and the evidence suggests it does, it necessarily belongs with the breeder, because owners cannot go back in time and redo it.

This does not mean that later experience is irrelevant, or that owners are powerless. It means that by the time a puppy comes home, some of the most influential conditions have already passed. From that point on, owners are working with a starting point they did not create. Asking what that starting point looks like is not a moral judgement; it is a practical question about what the dog will have to carry through ordinary life, and what may later require careful management.

Research suggesting higher prevalence and severity of noise sensitivities in mixed-breed and rescue dogs is best understood in this light. These patterns do not reflect anything inherent to adoption or rescue. Rather, they appear to reflect stacked biological and environmental risk: genetic background, the timing and quality of early experience, later acquisition, and differences in early rearing and training.

However, not all rescue dogs share the same developmental history. A dog raised on the street or in a busy urban setting may, in some cases, have experienced a rich and continuous backdrop of everyday sound during early development—conditions that can buffer against later noise sensitivity. By contrast, dogs from restricted early environments, such as backyard breeding operations or large-scale commercial breeding facilities, may have had far less opportunity for safe, developmentally appropriate exposure.

However, not all rescue dogs share the same developmental history – without knowing the details of early life, broad categories tell us very little. A dog raised on the street or in a busy urban setting may, in some cases, have experienced a rich and continuous backdrop of everyday sound during early development, which can buffer against later noise sensitivity. By contrast, dogs from highly restricted early environments (such as backyard breeding operations or large-scale commercial breeding facilities) may have had far less opportunity for safe, developmentally appropriate exposure.

In short, broad categories tell us very little without context and detail – and the goal of this article has been to empower you to ask more questions.

Closing thoughts

Early rearing is therefore not about doing more, but about doing the right things at the right time, informed by how development actually works. Doing right by the dog depends on developmental understanding, not just good intentions – timing, context, and the puppy’s internal state determine whether experience supports healthy organisation or adds strain.

Understanding early development, then, is not just a matter of knowing when stages occur, but why they exist. In natural conditions, early development unfolds within a carefully matched environment: limited mobility, close social buffering, and a stable sensory backdrop. Domestic breeding removes much of that context: puppies are no longer raised in dens, exposed only to the sounds and rhythms of a single, predictable territory. What breeders now provide in early life is therefore not an extra, nor an attempt to accelerate development, but a necessary replacement for what has been stripped away.

Ultimately, this is why I have written this article at all. We ask dogs to live in a world that is louder, busier, and more demanding than anything they evolved for – fireworks are just the most obvious reminder. If we expect dogs to cope with that world, then the least we can do is make sure the foundations we give them are fit for purpose.

The problem is not a lack of care or effort. It is that much of what matters most happens early, quietly, and out of sight — before owners are involved, and without a shared understanding of what good early development actually requires. When that knowledge is missing, outcomes depend on luck, and the cost of that luck is paid by dogs later in life. Treating early dog rearing as skilled, time-limited work is not about blame, and it is not about raising standards to exclude people. It is about recognising responsibility where leverage exists.

If we are serious about improving dogs’ welfare in modern life, this is one of the few places where doing better early genuinely makes later life easier — for dogs and for the people who live with them.

References & further reading

Please note: I have not made detailed in-line references in this article simply because of the time it takes – my blog does not usually have a huge volume of readers, so I balance the time and effort it takes to write these longer educational pieces with the number of people who will actually benefit from the additional time of being academically precise with referencing. If there is a particular claim that you’d like me to point you to, please contact me and I’d be happy to do so.

Alves, J. C., Santos, A., Lopes, B., & Jorge, P. (2018). Effect of Auditory Stimulation During Early Development in Puppy Testing of Future Police Working Dogs. Topics in companion animal medicine, 33(4), 100–104. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.tcam.2018.08.004

Bischof H. J. (2007). Behavioral and neuronal aspects of developmental sensitive periods. Neuroreport, 18(5), 461–465. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNR.0b013e328014204e

Bottjer S. W. (2002). Neural strategies for learning during sensitive periods of development. Journal of comparative physiology. A, Neuroethology, sensory, neural, and behavioral physiology, 188(11-12), 917–928. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00359-002-0356-0

Chaloupková, H., Svobodová, I., Vápeník, P., & Bartoš, L. (2018). Increased resistance to sudden noise by audio stimulation during early ontogeny in German shepherd puppies. PloS one, 13(5), e0196553. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196553

Dietz, L., Arnold, A.K., Goerlich-Jansson, V.C., & Vinke, C.M. (2018). The importance of early life experiences for the development of behavioural disorders in domestic dogs. Behaviour, 155, 83-114.

Foyer, P., Bjällerhag, N., Wilsson, E., & Jensen, P. (2014). Behaviour and experiences of dogs during the first year of life predict the outcome in a later temperament test. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 155, 93-100.

Freedman, D. G., King, J.A. & Elliot, O. (1961). Critical period in the social development of dogs. Science, 133(3457), 1016–1017. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.133.3457.1016

Guardini, G., Bowen, J., Mariti, C., Fatjó, J., Sighieri, C., & Gazzano, A. (2017). Influence of Maternal Care on Behavioural Development of Domestic Dogs (Canis Familiaris) Living in a Home Environment. Animals : an open access journal from MDPI, 7(12), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani7120093

Harvey, N. D., Craigon, P. J., Blythe, S. A., England, G. C., & Asher, L. (2016). Social rearing environment influences dog behavioral development. Journal of Veterinary Behavior, 16, 13-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2016.03.004

Hensch T. K. (2005). Critical period plasticity in local cortical circuits. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 6(11), 877–888. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1787

Hong, H., Guo, C., Liu, X., Yang, L., Ren, W., Zhao, H., Li, Y., Zhou, Z., Lam, S. M., Mi, J., Zuo, Z., Liu, C., Wang, G. D., Zhuo, Y., Zhang, Y. P., Li, Y., Shui, G., Zhang, Y. Q., & Xiong, Y. (2023). Differential effects of social isolation on oligodendrocyte development in different brain regions: insights from a canine model. Frontiers in cellular neuroscience, 17, 1201295. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2023.1201295

Howell, T. J., King, T., & Bennett, P. C. (2015). Puppy parties and beyond: the role of early age socialization practices on adult dog behavior. Veterinary medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 6, 143–153. https://doi.org/10.2147/VMRR.S62081

Knudsen E. I. (2004). Sensitive periods in the development of the brain and behavior. Journal of cognitive neuroscience, 16(8), 1412–1425. https://doi.org/10.1162/0898929042304796

Puurunen, J., Hakanen, E., Salonen, M. K., Mikkola, S., Sulkama, S., Araujo, C., & Lohi, H. (2020). Inadequate socialisation, inactivity, and urban living environment are associated with social fearfulness in pet dogs. Scientific reports, 10(1), 3527. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-60546-w

Riemer, S. (2019) Not a one-way road—Severity, progression and prevention of firework fears in dogs. PLoS ONE 14(9): e0218150. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218150

Riemer, S. (2020). Effectiveness of treatments for firework fears in dogs. Journal of veterinary behavior, 37, 61-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2020.04.005

Riemer, S. (2023). Therapy and Prevention of Noise Fears in Dogs—A Review of the Current Evidence for Practitioners. Animals, 13(23), 3664. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13233664

Serpell, J., Duffy, D. L., & Jagoe, J. A. (2016). Becoming a dog: Early experience and the development of behavior. The domestic dog: Its evolution, behavior and interactions with People, 2, 93-117.

Stolzlechner, L., Bonorand, A., & Riemer, S. (2022). Optimising Puppy Socialisation-Short- and Long-Term Effects of a Training Programme during the Early Socialisation Period. Animals : an open access journal from MDPI, 12(22), 3067. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12223067

Strain, G. M., Tedford, B. L., & Jackson, R. M. (1991). Postnatal development of the brain stem auditory-evoked potential in dogs. American Journal of Veterinary Research, 52(3), 410-415. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2035914/

Salonen, M., Mikkola, S., Niskanen, J. E., Hakanen, E., Sulkama, S., Puurunen, J., & Lohi, H. (2023). Breed, age, and social environment are associated with personality traits in dogs. iScience, 26(5), 106691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.106691