Parts 1 and 2 of this series were about understanding what food reactions actually are, how to identify them and what is in the food that might be triggering them. This part is about what to do with that understanding when your dog is in front of you and you suspect something might not be quite right with them and their food.

Please note: I’m sharing this information as if a friend or one of our puppy families came to me with questions – it is not meant to replace veterinary advice. If your dog has a significant or persistent problem, please consult a canine nutritionist or veterinary dermatologist, because the differential diagnosis between food allergy and environmental atopy in particular often requires clinical input that a blog post cannot provide.

What a blog post can do is give you a framework for observing systematically and ruling out simpler mechanisms before concluding that a food allergy is the explanation, so that if you do consult a professional, you arrive with better information than ‘I think it might be chicken.’ If your dog has strong, immediate, or severe reactions to food, please skip straight to the professional.

Why the mechanism matters before the intervention

If your dog has been reacting to food and you have spoken to a vet about it, there is a reasonable chance you left the consultation with a recommendation to try a novel protein or hydrolysed diet.

That is a sensible first-line suggestion. A ten-minute consultation is a real constraint, and giving an owner something concrete to try within that time is exactly the right instinct. What the consultation usually cannot do is explain the full picture of why the reaction might be happening, which is what determines whether the novel protein approach is the right next step or whether something else would work better.

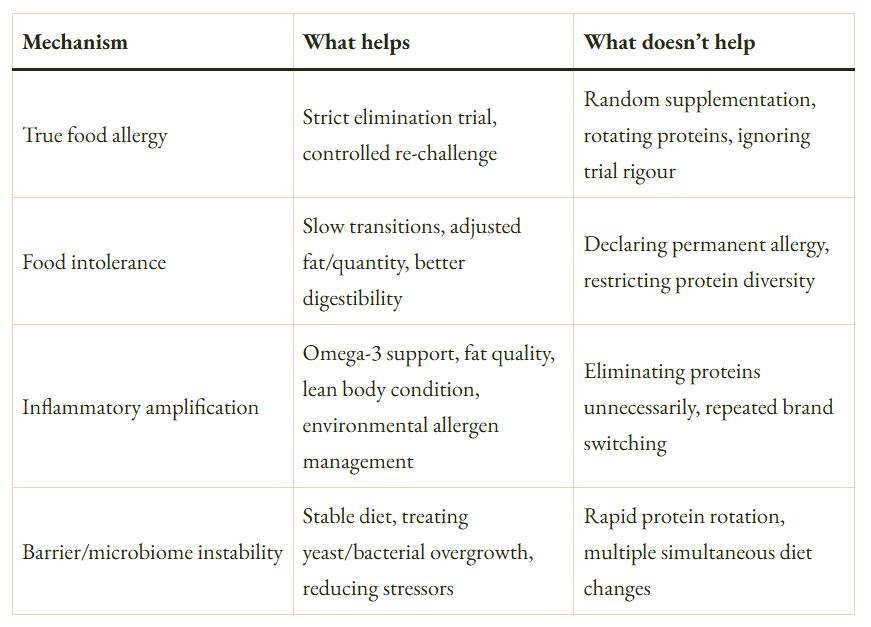

The most useful thing to understand before changing anything is that most dogs with food-related symptoms are dealing with inflammatory amplification, barrier instability, or intolerance rather than true protein-specific allergy, and none of those three mechanisms require a novel protein elimination trial to resolve. Protein-specific allergy is the mechanism most people assume when they hear “food reaction,” partly because it is the most concrete-sounding explanation and partly because it maps onto the most visible intervention: switch the protein. Yet… it is actually the least common of the four mechanisms covered in Part 1, and treating the other three as if they were allergy tends to make them more complicated rather than less.

If your dog has no current problems

The best time to think about food reactions is before they happen, because the conditions that make sensitisation more likely are mostly preventable rather than inevitable.

The mechanism that explains why beef and chicken top every food allergy list is exposure frequency: the proteins a dog has encountered most often across its lifetime are the ones most likely to appear in its allergy history, because sensitisation requires prior exposure. Keeping that exposure frequency distributed across multiple proteins rather than concentrated on one or two reduces the probability that the immune system develops a specific response to any of them. This does not require rotating complete diets or spending more money. It means that the variety of proteins across everything the dog eats — including treats, chews, and any toppers or supplements — adds up over time in a useful direction.

With puppies there is an additional practical reality: complete food options for very small dogs are limited, which means the base diet may not offer much variety by itself. Building protein diversity through treats and chews while the puppy is young is a realistic approach that works within that constraint rather than against it. Most people do not think of treats as part of the protein exposure picture at all, which matters both for prevention and, later, for investigation: treats are one of the most common reasons an elimination trial fails without the owner understanding why.

A concern sometimes raised in breed communities is that feeding wide variety early in life uses up proteins that might be needed later for an elimination trial, and that it is therefore wiser to restrict variety in order to preserve novel protein options. The logic works in one direction but fails in the other: restricting variety means feeding the same proteins repeatedly, which is the mechanism that drives sensitisation in the first place. The risk being managed by restriction is that a future elimination trial becomes harder. The risk created by restriction is that an allergy develops that would not have developed under variety. Those are not equivalent tradeoffs, because hydrolysed protein diets exist precisely for cases where no genuinely novel protein can be identified, and because proteins such as insect meal or specific game species remain novel even for dogs fed wide variety across conventional meat sources.

When a dog is already reacting: why changing protein is usually not the first step

Changing the food immediately is frequently counterproductive, and understanding why requires going back to the threshold model from Part 1:

Allergy risk ≈ Genetic predisposition × Barrier integrity × Inflammatory baseline × Allergen exposure

Every complete diet switch changes multiple variables at once: the protein source, the fat profile and its oxidation state, the carbohydrate composition, the palatants, and the microbial composition of the gut, which takes weeks to months to stabilise after a dietary shift. If the dog is already in a state of immune instability or compromised barrier function, introducing new proteins during that period increases the probability of sensitisation to those new proteins, because the immune system is encountering novel antigens in an inflammatory context rather than a tolerant one. The dog that appears to react to everything after multiple rapid switches has not necessarily developed allergies to all of those proteins. In many cases it has developed sensitisation to proteins it encountered during a period of instability that might otherwise have been tolerated without incident.

The more effective first step is stabilisation: resolving the conditions that are amplifying reactivity, rather than immediately searching for the trigger protein. Stabilisation typically involves treating any yeast or bacterial overgrowth early, because these are markers of barrier dysfunction rather than cosmetic problems and they sustain the inflammatory context that makes further sensitisation more likely. Adding a marine omega-3 source addresses the omega-6 dominance issue covered in Part 2. Holding the diet steady, storing food properly, and maintaining lean body condition (adipose tissue produces inflammatory cytokines that contribute to baseline inflammatory tone) reduce the overall load on the threshold.

Reading the pattern before you act

Before changing the diet at all, the pattern of symptoms is worth observing carefully because it points toward different mechanisms and therefore different responses.

Symptoms that are seasonal (appearing or worsening at the same time each year and then resolving ) are much more likely to involve environmental allergens such as pollen, grass, or dust mites than food. True food allergy does not follow seasonal patterns, because the exposure (the food) is constant rather than cyclical. A dog whose skin and ears flare every summer is more likely reacting to something in the environment than to whatever is in its bowl, and switching proteins will not address that driver even if the timing coincidentally overlaps with a diet change.

Symptoms that started after a specific destabilising event (a move, a course of antibiotics, a yeast infection, a period of rapid diet switching) suggest barrier instability or microbiome disruption rather than a new allergy developing from nothing, and stabilisation is the appropriate response before anything else.

Symptoms that are dose dependent, meaning they are worse with larger quantities and absent or mild with small amounts, point toward intolerance rather than allergy. True IgE-mediated allergy does not reliably scale with dose in the same way; even a small amount of the allergen can trigger a significant response.

The single most informative test before an elimination trial is one that most people skip: giving the suspected protein (usually chicken or beef) as plain cooked muscle meat, without any other ingredients, and observing whether the same symptoms reproduce. If they do not, the protein is unlikely to be the primary allergen, and the reaction to the kibble was driven by something else in the formula. If they do reproduce reliably, that is a meaningful signal and a legitimate basis for proceeding to a full elimination trial.

If symptoms improve substantially with stabilisation, that tells you something useful: the problem was likely inflammatory amplification or barrier instability rather than protein-specific allergy, and the appropriate long-term management is the variables that control those mechanisms rather than a permanent protein restriction. If symptoms persist consistently after several weeks of genuine stabilisation, that points toward a protein-specific component and is the appropriate point to consider an elimination trial.

What a proper elimination trial actually requires

If stabilisation has not resolved symptoms and the plain cooked protein test points toward a genuine protein-specific component, an elimination trial is the appropriate next step.

This is not the same thing as switching to a food with a different protein on the label. A valid elimination trial requires a single novel protein source (one the dog has genuinely not encountered before, which requires checking the full ingredient history including treats, chews, and palatants) or a hydrolysed protein diet, in which proteins are broken into fragments small enough that the immune system cannot recognise them as allergens. All other protein sources must be excluded completely for the duration, including treats, flavoured chews, flavoured toothpaste, and flavoured medications, because even small amounts of the reactive protein are enough to maintain sensitisation and produce a false negative result. The trial needs to run for a minimum of eight to twelve weeks, because skin symptoms in particular take weeks to downregulate even after the trigger is removed, and assessing the outcome before that point produces unreliable results.

The step that is most often missed is re-challenge: deliberately reintroducing the original protein at the end of a successful trial to confirm that symptoms return. Without re-challenge, an improvement during the trial could reflect reduced fat oxidation from a higher quality formula, microbiome stabilisation from a steadier diet, seasonal resolution of environmental symptoms, or reduced inflammatory load from any number of variables. Re-challenge is what distinguishes a confirmed food allergy diagnosis from an observation that symptoms improved when something changed.

Hydrolysed diets are useful specifically because they solve the “no novel protein available” problem that arises in dogs with extensive feeding histories: the protein source is irrelevant because the fragments are below immune recognition size. They are diagnostic tools and short-term management options rather than permanent solutions, and most dogs do not need to stay on them indefinitely once the diagnostic picture is clear.

A decision framework

The following is a simplified version of the questions worth working through before concluding that a dog has a food allergy and before committing to a management strategy based on that conclusion.

- Are the symptoms seasonal? If yes, investigate environmental allergens as the primary driver before food. If no, continue.

- Did symptoms start after a destabilising event such as antibiotics, a yeast infection, rapid diet switching, or rehoming? If yes, stabilise barrier and microbiome first and reassess. If no, continue.

- Are symptoms dose dependent? If yes, intolerance is more likely than allergy. Identify the threshold rather than eliminating the protein entirely.

- Does plain cooked single-protein muscle meat reproduce the symptoms in isolation? If no, the protein is probably not the primary driver. Investigate the formula variables covered in Part 2. If yes, a protein-specific component is plausible and an elimination trial is warranted.

- Has stabilisation — omega-3 supplementation, barrier support, steady diet, lean body condition — been tried for at least four weeks before drawing conclusions? If no, try that first.

If you have reached the bottom of this framework and the evidence still points toward protein-specific allergy, an elimination trial with proper methodology and re-challenge is the appropriate next step, ideally with veterinary oversight because the differential between food allergy and environmental atopy, which affects a much larger proportion of allergic dogs, sometimes requires clinical testing to resolve.

This series has covered a lot of ground because the subject is genuinely complex and the shorthand version — “my dog has a chicken allergy” — compresses several different mechanisms into a single phrase that does not distinguish between them. The framework above is a starting point, not a diagnostic protocol, and a vet who understands the full picture is worth consulting if you are working through it with a dog that is genuinely struggling.

The goal throughout has been to give the vocabulary and the framework to ask better questions rather than to add anxiety about what is in the bowl.