The key reason why breed standards matter even when you are focused on the potential performance of a dog is that not all dogs are physically suited to the activities we want to do with them. I’ve previously written about why structure matters even for working spaniels – it’s not just about performance, unless you don’t really care about dog wellbeing.

Evaluating both temperament and conformation is key to matching dogs with activities suiting their physical and mental makeup. However, in the working spaniel world many people strongly believe that working ability is more important than appearance – dismissing breed standards as an irrelevance of the vain world of show dogs.

This a huge mistake and an oversight that has serious consequences for dog wellbeing. While it is possible for dogs with great drive to succeed despite conformational flaws, it is often at great bodily cost because a strong working drive may push a dog to override its physical limitations through intense motivation to hunt, herd, track game, etc.

Sound structure optimises longevity, safety and achievement: although a balanced dog will still tire from work, it will recover with rest while an imbalanced dog with great drive will shine briefly before typically experiencing front end breakdown that shortens its working life. There is no such thing as the perfect dog, but we can try to aim as high as as possible for the sake of the dog’s wellbeing. Structural weaknesses are not measure of a dog’s worth or lovability – for me it’s quite the opposite, because I wish for all dogs to have a structure that is optimised for wellbeing even into old age.

Most breed standards are designed by committee, so it’s important to be understand how the different aspects of the dog’s structure when both choosing a dog with the goal of engaging in dog sports as well as when making breeding choices.

In the past year, I’ve become increasingly interested in dog structure and movement, so I’ve written this article as an exercise to practice by analysing the Polish Hunting Spaniel breed standard and to share a lot of the resources to hopefully help others access the same information. Books on this topic are not always easy to find and they’re also often expensive, so the information is effectively gatekept from all but those who are especially persistent even though it would benefit every dog owner by helping them understand their dog’s structure and the impact of the dog’s conformation on well-being (e.g. susceptibility to injuries and the potential need for special conditioning). There are additional resources in each section for those who want to learn more.

And if the information in this article leads you to recognize your own dog is unsound in some way, it does not make them less deserving of love; rather, it should empower more thoughtful care – you’ll better understand their structural weaknesses, how those may negatively impact them, what may have caused any injuries, and how to provide preventative support for their optimal health.

Jump to specific sections

Body: Topline, back and loin, Croup, Chest, underline and belly, tail

Front assembly: Shoulders, Upper Arms, Forearms, Elbows, Pastern and wrist, Feet

I’ll use pictures of Grace throughout because I do not want to highlight anyone else’s dog and as Dutch and Belgian champion, she meets the breed standard. Most of them are not properly “stacked” (positioned) which makes them harder to analyse, but writing this article took forever so I picked what I already had on WordPress – I may add better pictures at a later time.

Main sources for this article

Structure In Action – The Makings Of A Durable Dog

Structure of The Dog: Basic Course

Canine Sports Medicine and Rehabilitation

What’s Your Angle? Understanding Angulation and Structure for The Performance Dog

Evaluating Puppy Structure (webinar)

Built to Last: The Basics of Canine Conformation & Anatomy (American Kennel Club)

General appearance

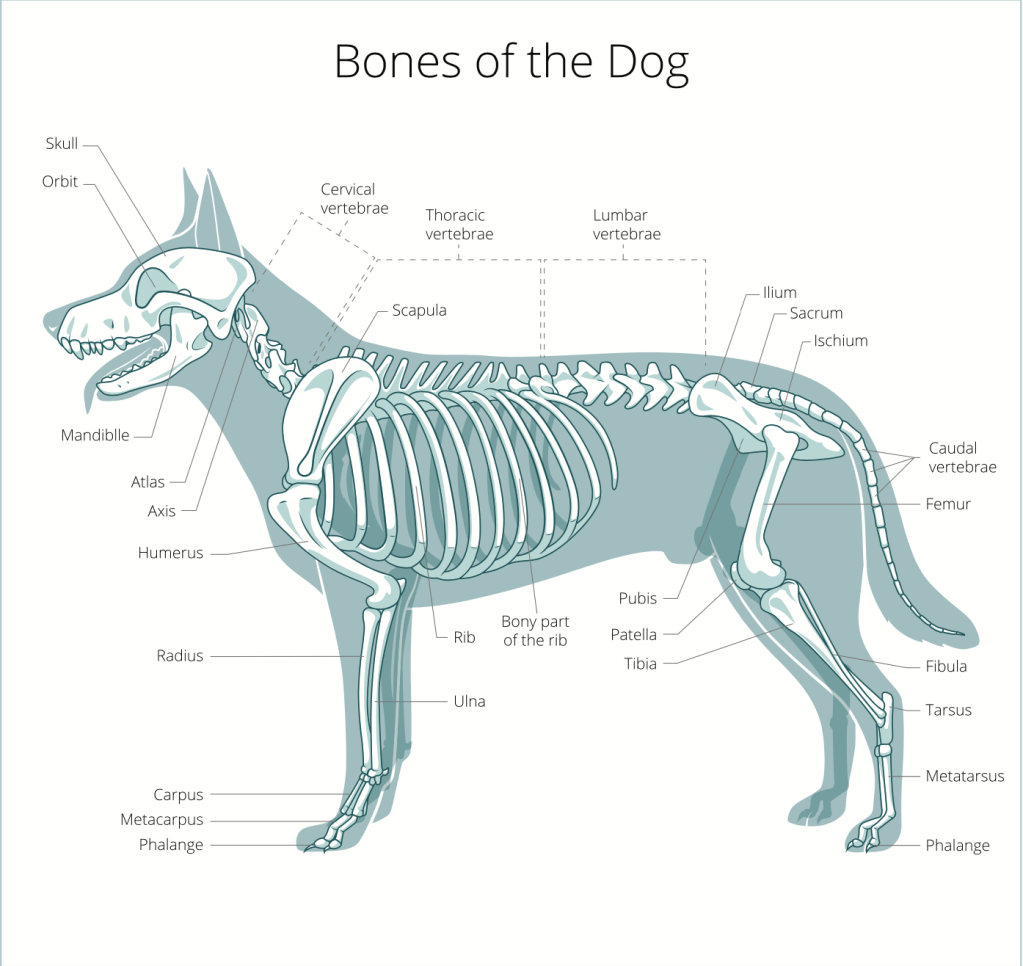

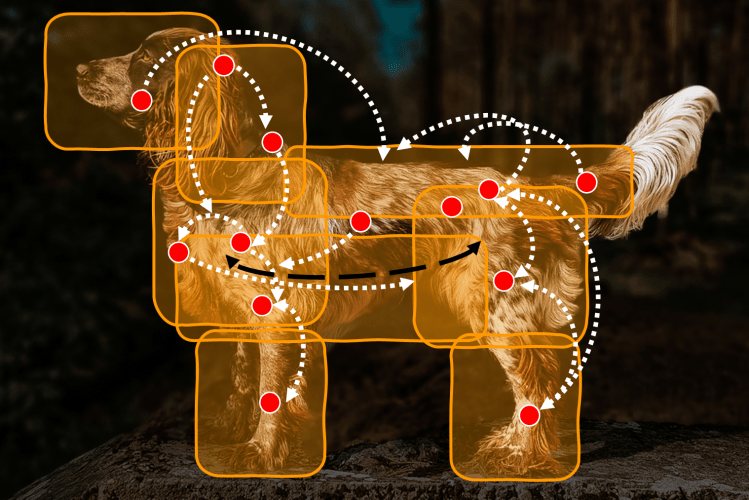

A dog’s interconnected structure functions as a system of levers and pulleys, with the back forming a vital bridge between the front and rear assemblies.

Even front to rear bone length ratios create balance suitable for each breed, though ideal proportions vary. Form follows function, so we need to consider a breed’s purpose, characteristic gait and needs. The dog is designed as a cohesive, moving whole so we need to evaluate anatomical relationships, overall structural harmony and soundness to understand breed-specific performance.

Medium-sized dog, of compact built providing great mobility and resistance for difficult working conditions, mainly in the fields, meadows, rushes, bogs and water.

Movement when trotting should be free, flexible in joints, agile and parallel. The limbs move freely, presenting fairly long stride, but should not be lifted high above the ground. The movement must be economical. When working with a hunter, the dog moves easily and quickly, low above the ground, on bent legs, crouching and sitting on the ground, alternately with sudden changes of direction, stopping or springy jumps.

In this general appearance section, the first sentence sets the scene for the rest of the breed standard – it provides context for the intended function of the form that the rest of the standard describes. Before reading on, pause to imagine what those difficult working conditions look like: what demands on a dog’s body would it place if their job requires them to move fast in fields, meadows, rushes, bogs and water? Keep this in mind as you read further!

Proportions: The dog of moderate size (allowing him to move unnoticed in dense bushes and tall grasses), rectangular build, the ratio of height at withers to length of the body is 9:10-12.

Read more about evaluating the proportions and landmarks of a dog

VIDEO: Canine Structure and Anatomy – this video is a good introduction

Evaluating the Structure of the Canine Athlete – shows three methods of evaluation

Measuring Proportions and Finding Landmarks (Size, Proportion, Substance)

Measuring Proportions and Finding Landmarks: Part 2 (The Head, Chest & Forequarters)

Measuring Proportions and Finding Landmarks | Part 3 (The Topline, Underline & Rear Assembly)

The limbs of fairly strong bone; the ears hanging, covered with fringes of longer hair. The feathering is present also on the tail, belly and back of the legs. The coat colour is most frequently chocolate roan with patches (brown with brown nose) of different shade, less often black roan. The fawn tan markings sometimes occur. The characteristic feature is the white tip of the tail.

Coat and nose colour: The chocolate roan colour is to allow the dog to blend into the environment most efficiently, and the dark colour of the nose is important because a nose without pigmentation offers little protection from the sun. In the PSM, the white tip of the tail is also functional because it allows the hunter to see the dog’s location more easily in tall grass – a white tip is more visible than brown!

Bone: If dogs that do high impact activities are too light boned, they are at a higher risk of concussion injuries, shin splints and stress fractures. In addition, the tendons, ligaments and muscles don’t have as effective of a lever system which reduces muscle power and stamina. Although making dogs lighter might be beneficial for improving chances of success in a sport such as agility, it may come at an unpredictable cost to the dog’s health.

Read more

Form Follows Function Part 5: The Hands on Exam – Training Your Hands to Feel What You Can’t See

Head

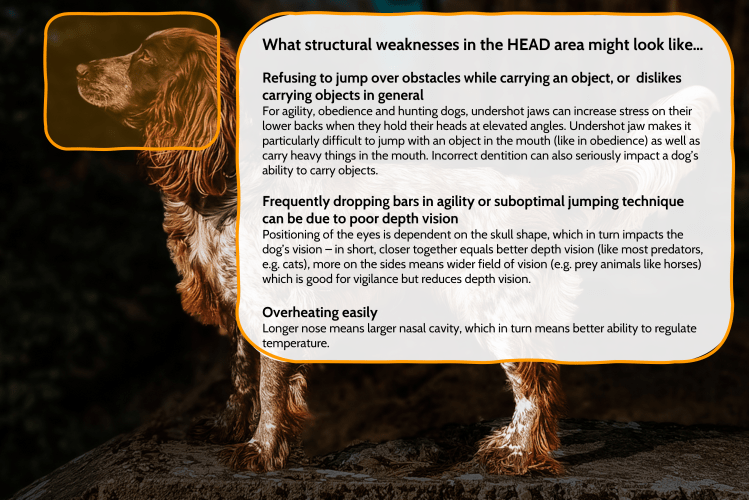

Form follows function, so optimal skull and muzzle proportions should match breed purpose and capabilities. Evaluating head structure provides insight into a dog’s suitability for particular roles because skull and muzzle conformation are connected to overall function. For example, skull shape impacts a dog’s vision through eye positioning and the length, width and depth of the muzzle impact scenting potential, strength of bite, and capacity to carry objects.

Head: Noble, quite large but in proportion to the body.

Skull: Same length as the muzzle but slightly convex. The occiput well defined.

Stop: Slightly pronounced.

Skull shape is linked to the positioning of the eyes which, in turn, are determined by the purpose of each breed in terms of the field of vision and depth perception required. For example, sighthounds have a 270-degree vision while the Pekingese have 190 degree vision, with most breeds somewhere in between. Dogs hunting by sight require a wider field of vision than those hunting by scent, while depth of vision is important for dogs moving in varied terrain like the spaniel, so the skull shape must reflect their purpose.

Muzzle and cheeks: Well filled, deep and somewhat blunt. The nose bridge straight with the area below the eyes is well filled in and nicely chiselled. The ratio of length of muzzle to length of the skull is 1:1. Quite lean, filled, visibly chiselled cheeks below the eyes, merging gently into the cranial region of the skull.

Jaws/Teeth: Teeth white, quite large. Jaws fairly broad with almost parallel corresponding rows of premolars and molars, which at the incisor region are set in a slightly rounded arc.

The bite natural (scissors bite, pincer bite acceptable). Full dentition desirable but not required.

Dogs with longer muzzles generally have larger nasal cavities, which provide more room for specialized scent receptors and a greater surface area for scent molecules to interact with. Longer muzzles may have a higher olfactory flow rate, allowing them to sample and process scents more effectively. (Source) However, the longer and narrower the head, the weaker the jaw will be which is why it is important for a breed standard to define the ratio of muzzle to length of skull. This ratio is also the same as in wolves.

The angle of the cheekbone (zygomatic arch) affects the strength of the jaw – the flatter the arch, the less strength there is in the jaw. It is desirable for a spaniel to have a soft mouth, so flatter cheekbones are appropriate.

The more correct a dog’s mouth is, the more comfortable they are because abnormal tooth alignment can mean discomfort when it comes to holding things in the mouth. More specifically for agility, obedience and hunting dogs, things like undershot jaws can increase stress on their lower backs when they hold their heads at elevated angles – jumping with an object in the mouth (like in obedience) is particularly difficult. Additionally, carrying heavy things in the mouth is harder with an undershot jaw.

Specifying teeth in the breed standard is important because it leads breeders to pay attention to them – otherwise, there is a risk of ignoring them and the standards can then decrease, leading to poorer teeth each generation.

Eyes: Medium sized, not too deep set, almond or triangular-shaped, of friendly expression. The white of the eye is not visible. Colour from light to dark hazel, corresponding to coat colour. The eyelids fairly thick, well fitting to the eyeball.

A medium sized, almond shaped eye is less prone to injury as well as being easier to blink and keep warm, which is why it is common in most sporting, working and herding breed standards. A loose eye is much more prone to gathering debris than a tight eye.

Positioning of the eye is addressed above.

Nose: black or brown, according to the coat colour; large, protruding ahead of upper lip. The nostrils wide open and mobile.

Sporting breeds tend to have a requirement for a well-opened nose. Large nostrils increase the scenting ability of the dog as well as allowing for maximum air intake. For dogs who tend to work outdoors during the day, dark pigmentation of the nose is important.

Neck & withers

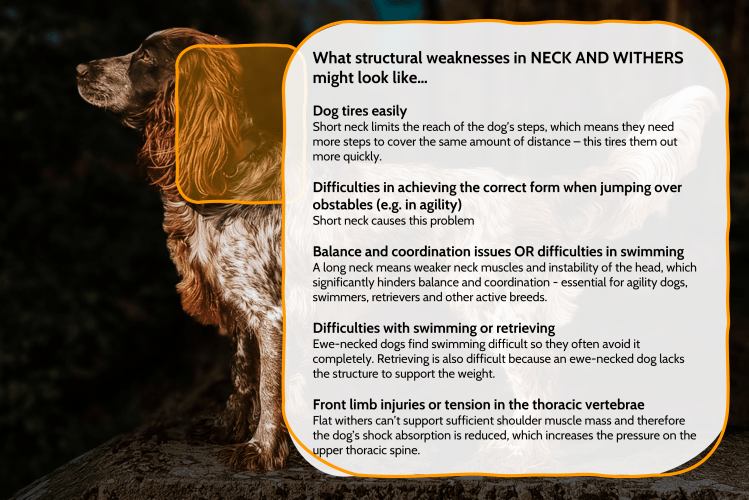

As with other parts of the dog’s anatomy, the design of the neck should reflect the purpose for which the breed was developed as well as being functional for the dog.

The length of a dog’s neck significantly impacts its movement: dogs with short necks often have straight shoulders, which limit their reach and stride. This conformation can be problematic for breeds needing endurance and efficiency to fulfill their purpose. A dog’s front foot falls only as far forward as its nose extends so a short neck means more steps to cover the same distance compared to a longer neck and stride. A short neck is also a problem for agility and obedience dogs as they’ll have difficulty achieving the correct form over jumps.

While a longer neck may seem desirable, it can negatively impact a dog’s anatomy and performance. Increased neck length is often due to elongation of individual vertebrae or greater spacing between them, rather than additional vertebrae. This can result in weaker neck muscles and instability of the head. A long, weak neck significantly hinders balance and coordination, which are essential for agility dogs, swimmers, retrievers and other active breeds.

An “ewe neck” is an undesirable extreme neck conformation where the ligaments between vertebrae are too long or loose. This allows excessive curvature of the neck, giving it a ewe-like appearance, often seen in poodles. To compensate, ewe-necked dogs hold their heads upright. However, this unnatural head carriage still reduces their forward reach and ground clearance while in motion. The instability of an ewe neck also impairs swimming ability, as well as carrying or retrieving heavy objects comfortably. The poor structural support leads to increased injury risk during demanding activities like hunting, field trials or agility. Ewe necks lack both the strength for weight bearing and the flexibility for free range of motion.

Even worse is the ewe neck where the ligaments holding the neck vertebrae in alignment are either too long or too loose. Ewe necked dogs often compensate by holding their heads upright, as seen in e.g. poodles. This upright neck carriage also affects a dog’s reach and ability to keep its feet close to teh ground when in motion. Ewe-necked dogs also can’t swim well, so they tend to avoid having anything to do with water. Additionally, they usually can’t carry anything heavy in their mouths comfortably and tehy are at greater risk of injury if they are active in field trials, hunting or agility – particularly if they need to retrieve, since they do not have the structure to support it.

Medium length, well muscled neck with oval cross-section, well fitted into the ribcage. The upper line of the neck is extended by the withers. The skin on the neck is lean, not forming folds nor dewlap.

The medium lenght neck appears longer due to the well defined withers. Withers should be well defined, gently merging into the neck and the back.

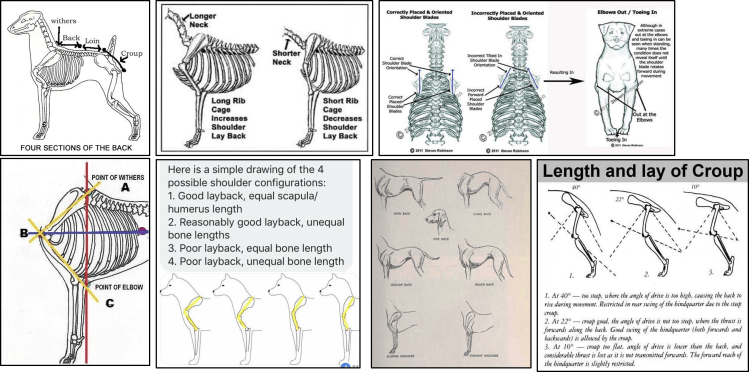

The height and structure of a dog’s withers significantly impacts movement and performance. Withers formed by vertebrae with longer spines allow for more robust muscle attachment, strengthening the front assembly. Ideal breed standards call for withers elevated above the back for this reason.

Flat withers result from short vertebral spines or insufficient shoulder blade length. Flat withers reduce forward reach and mobility in the front limbs. Dogs with flat withers are also prone to overuse injuries when participating in active sports. The decreased shoulder muscle mass and limited range of motion reduces shock absorption and increases pressure on the upper thoracic spine.

When evaluating conformation, wither height and muscle development should be considered for their role in providing strength and extension of the front assembly – the key is balancing sound structure with optimal mobility. Moderation is ideal, as anatomical extremes can negatively impact a dog’s functionality over time by altering muscle lengths. For example, high withers often coincide with straight shoulders. Note: breeds such as terriers whose original job doesn’t require them to traverse the woodlands all day long are an exception – read more at Shoulders.

Read more

Form Follows Function – Reach & Layback

Form Follows Function – Part 3: Hinquarters, Head, Neck & Spinal Column

Body

Rectangular build, the ratio of height at withers to length of the body is 9:10-12.

The ideal length of a dog’s back relative to its height is specific to each breed and its original purpose.

Leaving out chondroplastic breeds, there are three basic types: speed (e.g. sighthounds), strength (e.g. bull breeds) and endurance. Breed standards take into account original working roles when defining the ideal back-to-height ratio. A balanced and moderate ratio, neither too square nor too extreme, provides the most athleticism and correct gait for each breed.

Square dogs with back length equal to height are smooth, efficient trotters. The slightly longer backs of rectangular dogs increase stride length and speed while long, low backs reduce stride length and speed. However, square dogs require near perfect structure to move properly, while slightly longer backs allow more forgiveness in movement. Dogs taller than they are long lack the proper anatomical positioning for their legs and feet to function optimally.

Topline, back & loin

A dog’s back health starts with proper front and rear assembly structure. Other factors include suitable back length, proportional back-to-loin ratios, condition, and muscle development.

Topline: Smooth, not broken or visibly arched.

Back: Straight, neither saddled nor arched; fairly broad and well muscled.

Loin: Broad, muscular, of medium length. Slightly arched loin permissible.

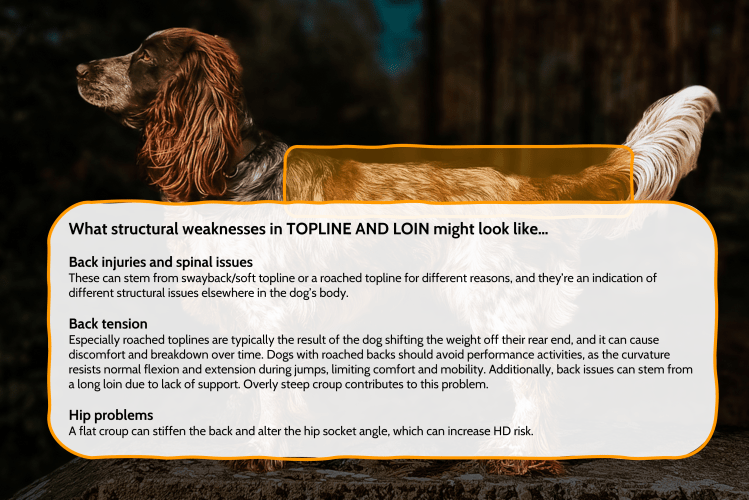

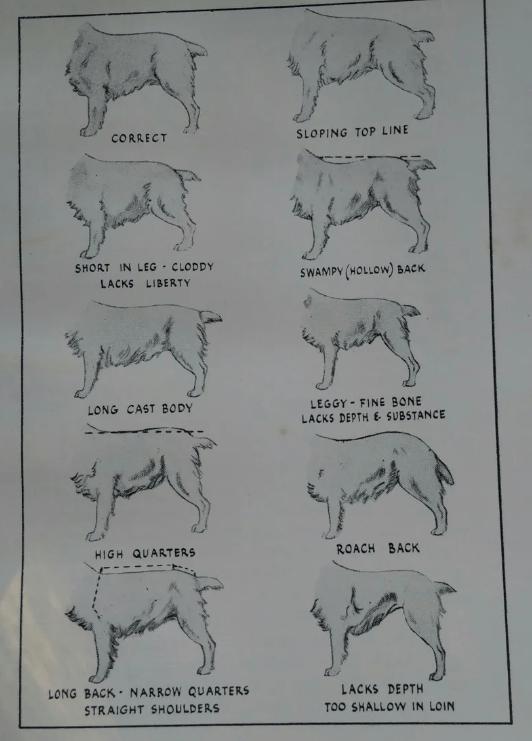

The term topline refers to the entire spinal column from the occiput to tail set, spanning the neck, withers, back, and croup. As the foundations beneath greatly influence topline appearance, flaws manifest from structural problems elsewhere. An optimal topline stems from sound overall conformation.

A sloped topline signifies structural imbalance between the front and rear assemblies because proper leg lengths and joint angulation should create a level topline in a balanced dog. A level topline allows for greater equilibrium, efficiency of movement, and reduced risk of injury. The goal should be harmonious front and rear assemblies that come together in a level topline and efficient gait – slopes indicate discrepancies in conformation that can hinder performance and soundness.

Curvature along the topline often indicates underlying structural issues. A swayback or soft topline stems from front assembly challenges and hinders efficient movement, potentially leading to back problems or injuries, especially in active dogs. Alternatively, a roached topline signifies rear assembly problems in breeds meant to have flat backs. The spine arches to shift weight off the rear, compensating for structural flaws. This compensation and the original issue can cause discomfort and breakdown over time. Dogs with roached backs should avoid performance activities, as the curvature resists normal flexion and extension during jumps, limiting comfort and mobility. However, some breeds like the Whippet have a muscular arch over the loin which allows spinal flexibility critical for covering ground during galloping. This conformational difference should not be confused with a roach.

Note: everything in a dog’s structure is connected, so you cannot simply select for a rear structure that resembles that of the whippet in another breed to increase the speed because it will result in other structural changes that may not be in line with the dog’s movement. Some dog sports people believe that a roached back helps with speed and jumping, but a dog who’s going to run fast needs to be able to be able to flex their spine in both directions. A level topline allows the dog to flex their spine fully to power from the rear and extend the back but if they already have a roached back, they can’t power from the rear as fully (specific source: webinar by canine sports medicine specialist Dr Chris Zink).

In most breeds, the ideal loin length is no more than one-third the length of the ribcage. This region between the end of the ribcage and hips lacks structural support beneath the spine. The proper loin ratio balances adequate spinal support with flexibility and agility. Excessive loin length impairs mobility and exposes the spine to greater risk of injury due to insufficient underlying connection.

Croup and tail set

Croup: Fairly broad and muscular, straight or sloping very gently to the base of the tail.

The croup and tail set are breed-specific, impacting balance and movement and ideal croup conformation must match the dog’s purpose.

Steep or over-rounded croups typically reflect underlying structural problems: the more dogs carry or position their rear legs under them, the more the croup will drop or round, and the more structural issues a dog has with its rear legs, the more pronounced the effect on the croup.

Sighthounds are the exceptions because they are suspension gallopers instead of trotters: their structure allows for quicker acceleration as the dog can easily get its rear legs under its body. However, when trotting, this steep pelvis prohibts a long backward swing of the rear leg and requires a straighter shoulder to keep the body in balance.

Regardless of breed, extremes should be avoided in breeding programs. For example, overly steep or rounded croups cause balance and compensation issues. Increased pressure on the rear leg joints creates greater downward pressure on the croup, making dogs more prone to lower back problems from unnatural spinal carriage.

Conversely, a flat croup can stiffen the back and alter the hip socket angle, potentially increasing hip dysplasia risks. Breeding for moderation preserves sound structure and function. Exaggerated features often have cascading detrimental effects.

Chest, underline and belly

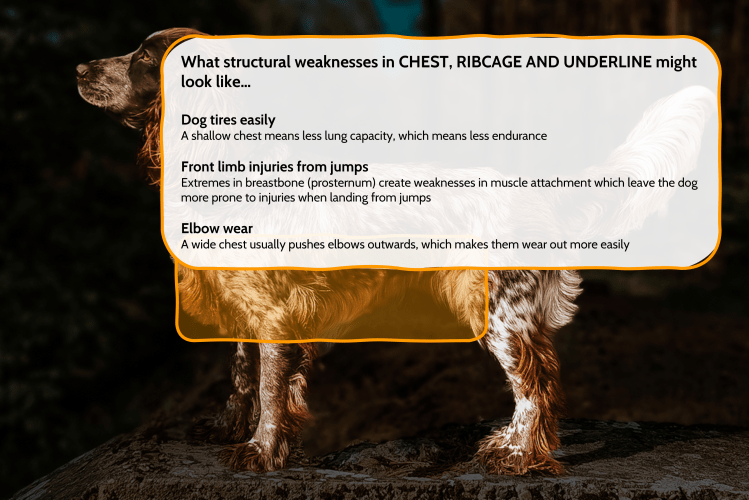

A correct chest and ribcage in the majority of breeds includes a depth of chest that reaches the elbows. The more correct the ribcage, the more lunch capacity, stamina and endurance.

Chest: Deep (in adult dogs often reaching below the elbow), of fairly long brisket, visibly extending to the rear, very capacious, with long and oblique ribs. The length of the body results from the length of the ribcage.

Underline and belly: only slightly tucked-up, flanks filled and quite short.

In most breeds the depth of the chest shoiuld reach the elbow because any less will impact lung capacity. A shallow chest will causes problems with lack of lung capacity, stamina and endurance, as well as diminishing the stability of the front because it affects how the upper arm connects to the chest. Without proper stability in the front, agility dogs are more likely to hit the ribs when they land from jumps (and the same would apply to hunting dogs jumping in nature). One particular feature of interest in the chest is the breastbone (prosternum) where extremes in any direction (too much or too little) will create some sort of weakness through more limited muscle attachment and strength as well as leaving a dog more susceptible to injuries when landing from jumps.

When the chest is too wide, the upper arm is prohibited from swining freely alongside the chst. This impeded upper arm movement diminishes the dog’s speed and length of stride.

A gradual, moderate underline optimizes health and performance. An overly tucked waist severely reduces lung capacity, restricts movement, and stresses the back. The ideal underline balances a tucked abdomen with full respiratory capability and freedom of motion while an overly exaggerated tuck stresses the back, compromises respiration, and limits athletic reach (examples).

Tail: Medium length, set not too high, reaching at least the hock joint, covered with moderately dense hair, often ended with a light tip. At the bottom a plume forming sparse and not too long fringes. When the dog is at rest, the tail is carried low and curved slightly upwards; in action may be carried a bit higher than the top line.

A dog’s tail plays a vital role in movement and balance as a counterweight for agility and stability. It prevents rear swing, assists jumping lift-off and landing, and acts as a rudder while swimming.

Dogs lacking sufficient tail length/strength experience spinal strain from lost counterbalance. Incorrect tailset also impairs balance – too high fails to properly counterbalance scenting dogs. The tail facilitates precision and fluidity in motion through integrated musculoskeletal dynamics. Working dogs require strong, long tails for adequate counterweight, especially in jumping or quick changes of direction. Tail set is the relationship between the sacrum and pelvis, and the angle at which it’s attached.

Read more

Pure Dog Talk podcast – episode on toplines

Vertical Movement in Toplines, Underlines, Croups and Tails

Moving toplines (incl. tail set and croup)

The truth about long backs and back pain

A Closer Look at the Canine Spine

Form follows Function: The Body of the Dog (the chest)

Front assembly

Sound structure requires congruous angles front to rear to optimize health, movement, and durability. Assessing integrated front and rear assembly conformation is crucial, since combining anatomical extremes risks health, performance and balance by restricting heart and lung space, reducing endurance.

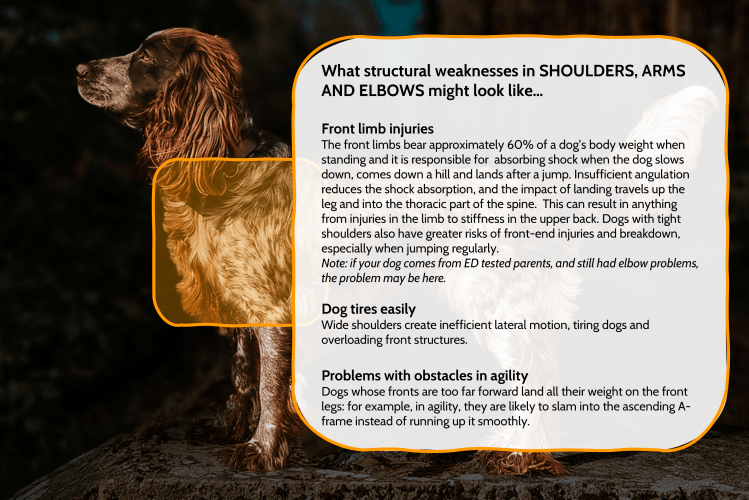

The front limbs bear approximately 60% of a dog’s body weight when standing and it is responsible for for absorbing shock when the dog slows down, comes down a hill and lands after a jump. Proper conformation requires harmonic angles front to rear to enable correct neck and back proportions, ideal front assembly position, ample forechest, and balanced toplines. It’s important to not fall into the trap of combining straight fronts with over-angled rears, contrasting front and rear angles because this imbalance creates an exaggerated, sloped topline and disrupts anatomical balance.

General appearance: Seen from the front straight and parallel. The distance from the elbow to ground is equal to the half of the height at the withers.

Most breed standards call for leg length equaling 50% of the dog’s height at the withers because this ratio optimizes muscle lengths and attachments for strength, reach and speed.

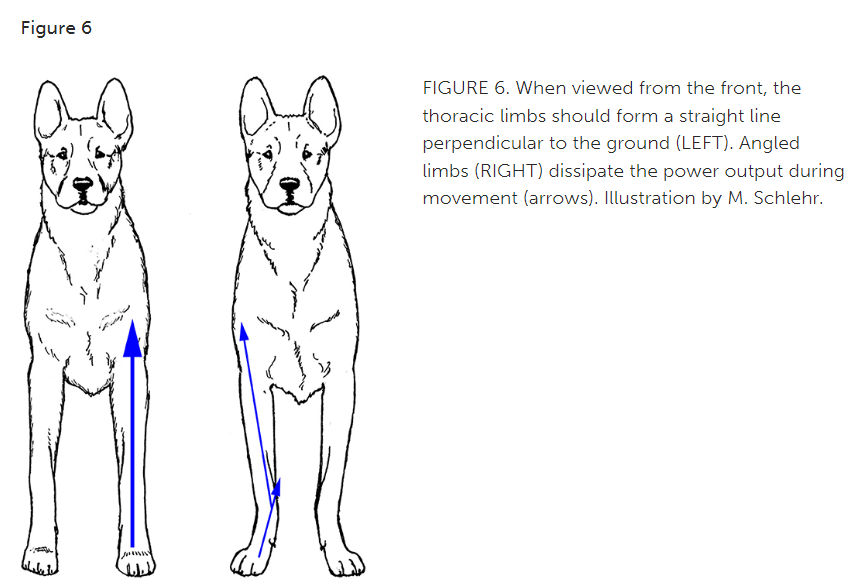

For a dog’s front legs to work properly, they need to stand straight and firmly grip the ground so that their muscles can push the weight forward in a straight line. If the front legs curve in or out, it wastes the muscles’ effort because legs pushing off at an angle is weaker and strains the joints more. If the front legs curve in or out, it wastes the muscles’ effort because legs pushing off at an angle is weaker and strains the joints more.

Shoulders

Well-laid back shoulders provide longer stride, less fatigue, and greater endurance that working breeds require.

Shoulders : Quite short and oblique, well muscled, close-fitting to the body. The angle of the shoulder joint is not very open.

Proper front angulation acts as shock absorption, reducing joint concussion compared to straight shoulders which create harsher impacts and higher injury risks. Appropriate shoulder layback is vital for performance, soundness, and preventing injuries in active dogs, though some variance suits different functions. Sufficient angulation promotes extension, protects joints, and supports durability.

Wide shoulders create inefficient lateral motion, tiring dogs and overloading front structures. Proper space between the shoulder blades allows them to move together as the dog lowers its head, enabling natural head carriage. Narrow shoulders restrict this shoulder joint motion. To compensate, dogs may turn their pasterns and feet outward, putting additional strain on the front legs. Dogs with tight shoulders have greater risks of front-end injuries and breakdown, especially when jumping regularly.

NOTE: Terriers are an exception in front structure: their front trades trotting efficiency for powerful digging. Despite the illusion of straight fronts, their shoulders have normal layback due to a shorter upper arm which enable the dog to dig more efficiently. High withers and tight shoulders are an acceptable compromise as terriers don’t run nose low like e.g. spaniels do but instead need firmer movement throughout the forequarter.

Upper arms: About the same length as shoulder blade or shorter, set obliquely back. Together with shoulders are closing gently sides of the ribcage.

Correct upper arm and shoulder proportions are crucial to sound front end conformation.

When the upper arm is shorter than the shoulder blade, it positions the front leg too far forward instead of properly under the chest. This misalignment places more stress on muscles and elbows. Short upper arms can cause inefficient wide gaits, crossing over, excessively high foot lift, and greater impact on the front assembly, particularly the pasterns and feet. Alternatively, overly long upper arms affect head and neck carriage by shifting the prosternum. Proper upper arm length matches the shoulder blade to correctly place the front leg under the chest for optimal function. The upper arm must balance the rest of the front assembly to distribute forces evenly and minimize strain.

If the upper arm sits too far forward in front of the ribcage, it cannot swing properly alongside it during forward motion which causes the front legs to swing outward in an inefficient “eggbeater” gait. Improper ribcage attachment also leaves the upper arm prone to injuries in activities like agility because without proper body support, the front assembly lacks strength and stability. Dogs whose fronts are too far forward land all their weight on the front legs: for example, in agility, they are likely to slam into the ascending A-frame instead of running up it smoothly.

Forearms: Straight, lean, of fairly strong bone, without protuberances, of oval cross-section, longer than upper arms.

The forearm supports body weight, provides propulsive force, and balances the front assembly.

In most breeds, it equals scapula length and comparing humerus to scapula length reveals shoulder angulation – if disproportionate, reach, lift, and head carriage are impacted while proper length enables correct leg placement under the chest for optimal function. As with all structures, moderation is best – too long or short humeri imbalance the front. While overly long forearms negatively shift neck and head position, short forearms misplace legs too far forward, reducing forechest, forward extension, and support under the chest, thus stressing muscles and bones. Shortened reach causes inefficient wide, rolling gaits that waste energy and can lead to long-term breakdown.

Elbows: Loosely attached to the body, not turning in nor out, set parallel with each other and with the middle axis of the body; constitute the beginning of parallel forearms.

Proper elbow conformation provides crucial front leg stability through a snug fit and controlled range of motion because the elbow functions as the hinge for lifting the front leg during gaiting and jumping.

For stability, the elbow should sit tightly against the chest and be minimally visible from any angle when standing or moving. Loose elbows result from overly long or lax ligaments and gently rocking the dog side-to-side can reveal instability as loose elbows pop outwards. The laxity causes inward foot rotation and puts pressure on the inner toes as well as allowing exerssive motion – this instability instability increases the risk of arthritis and tendonitis. Dogs with loose elbows also lack front support when landing jumps, increasing injury likelihood.

Metacarpus and carpus (aka pastern and wrist)

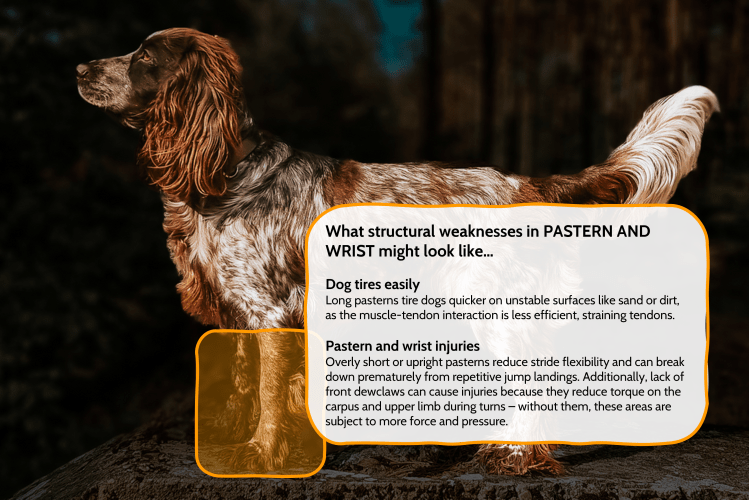

The pastern is very injury-prone, so any conformational flaws make dogs more prone to issues.

Metacarpus (Pastern): lean, of the thickness corresponding to the wrist and forearm, seen from the side straight or only slightly sloping forward.

Carpus (Wrist): Lean, compact and smooth, without traces of deformation and excessive protuberances.

Most standards call for short, slightly angled pasterns as ideal. Short pasterns place less weight on the lower leg, needing less muscle to lift and enabling greater speed, jumping, endurance, and soundness. Proper short, slightly sloped pasterns optimize performance through reduced weight, enhanced lift power, shock absorption, and joint soundness. They are a crucial foundation for durability.

Long pasterns tire dogs quicker on unstable surfaces like sand or dirt, as the muscle-tendon interaction is less efficient, straining tendons. Dogs with long pasterns should avoid rough terrain work like search and rescue. Overly short or upright pasterns reduce stride flexibility and can break down prematurely from repetitive jump landings.

When it comes to the wrist, the front dewclaws play an important role in stabilizing and supporting the carpus and wrist when dogs are moving at high speeds or taking sharp corners because they provide additional traction and resistance to rotation. While front dewclaws may seem non-functional when standing, they do contact the ground while cantering, galloping or jumping when dogs bear most weight on the front limbs. At these times, the dewclaws dig into the ground to help stabilize the front legs and reduce torque on the carpus and upper limb during turns.

Forefeet and hind feet

Forefeet: The toes rather long, elastic, little arched, with large, thick and firm pads. The nails quite thick, short, matching the coat colour. On the toes and between them, the longer hair forms so called “slippers”.

Hind feet: compact, slightly oval-shaped, the toes shorter than in forefeet, little arched and elastic. The nails thick, short, matching the coat colour. The pads large, thick and firm; longer hair between toes.

Dogs’ feet are shaped based on original function, with feet conforming to original terrain and movement patterns.

Foot shape gives insight into breed purpose and specialized adaptations for performance. Breeds moving over uneven ground tend to have compact, cat-like feet with evenly sized, tightly curled toes for maximum grip like knobby ATV tires. These aid agility in all directions. In contrast, sighthounds bred to run fast in straight lines have elongated hare feet, with longer third and fourth toes for extra forward propulsion like race car tires. While cat feet provide sturdy maneuverability, hare feet optimize straight-line speed and traction.

Read more

A Closer Look At The Canine Front

Canine Fronts Part II: A Well Laid Back Shoulder

Straight shoulders don’t reach – here’s why

Closer Look at the Humerus (Upper Arm) of a Dog

It’s What’s Up Front That Counts

Understanding (terrier) fronts & The Terrier Front

Rear assembly

Proper rear assembly conformation is crucial in rear drive animals like dogs, distributing forces soundly from the lumbar spine through the pelvis, thighs, and hock for fluid function.

General appearance: Seen from the rear straight and parallel with each other (parallel lines connecting the ischial and heel tuberosity on adequate side of the dog). Seen from the side are set slightly “behind the dog” and well angulated.

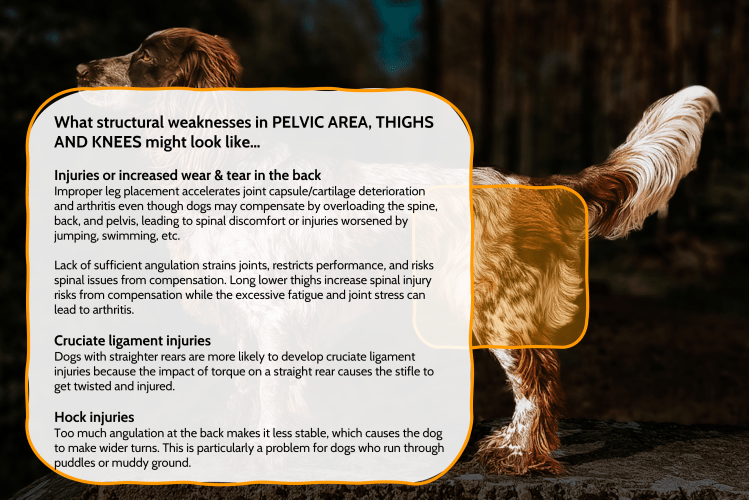

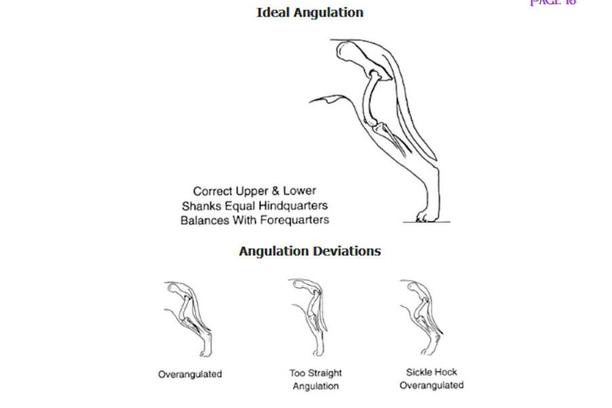

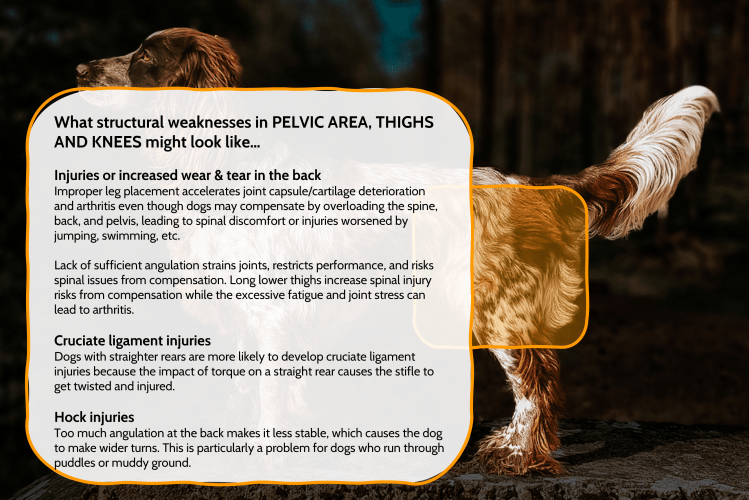

The croup, thighs, and hock must have suitable relative lengths and angles to enable effective propulsion. Proper angulation positions the rear for optimal function while insufficient conformation strains joints, restricts performance, and risks spinal issues from compensation. Thus, sound rear assembly is vital for force generation, movement quality, and whole body health. Importantly, correct hindquarter angulation is breed-specific as it should facilitate characteristic movement.

A dog with excessive rear angulation is less stable – they will make wider turns because they don’t have the stability to grip the ground and specifically with hunting dogs who may have to run through ponds and muddy areas that suck on their legs it often ends up in injuries to the hock. On the other hand, dogs with straighter rears are more likely to develop cruciate ligament injuries because the impact of torque on a straight rear causes the stifle to get twisted and injured.

Thigh and knee

Ideally, thigh bones are relatively equal in length because proper thigh length and angulation positions the rear for optimal function.

Thigh: Not too long, set wide apart, very well muscled.

Lower thigh: About the same length as the thigh or shorter; well muscled.

Stifle (Knee): The stifle joint lean and well pronounced, with marked angulation.

Improper leg placement accelerates joint capsule/cartilage deterioration and arthritis even though dogs may compensate by overloading the spine, back, and pelvis, leading to spinal discomfort or injuries worsened by jumping, swimming, etc

Short thigh bones place the legs too far under instead of behind the body and therefore less angulation which alters joint mechanics and causes abnormal wear. This insufficient rear assembly conformation strains joints, restricts performance, and risks spinal issues. On the other hand, excessive rear angulation from overly long bones strains joints and negatively impact movement and soundness. Overangulated dogs lack rear stability, struggling to turn tightly or quickly – the farther behind the foot is, the more stress on the stifle, hock, and hip joints. Like other rear flaws, long lower thighs increase spinal injury risks from compensation while the excessive fatigue and joint stress can lead to arthritis.

A longer lower thigh makes dogs move in an inefficient sickle pattern, stand cow-hocked, or lead with one foot to generate thrust against the longer lever arm. This abnormally stresses the stifle and shortens the rear stride by pulling down the ischium muscle, which can lift the front assembly. Increased oscillation also vibrates the joints, tendons, and ligaments.

Hock joint and rear pastern (metatarsus)

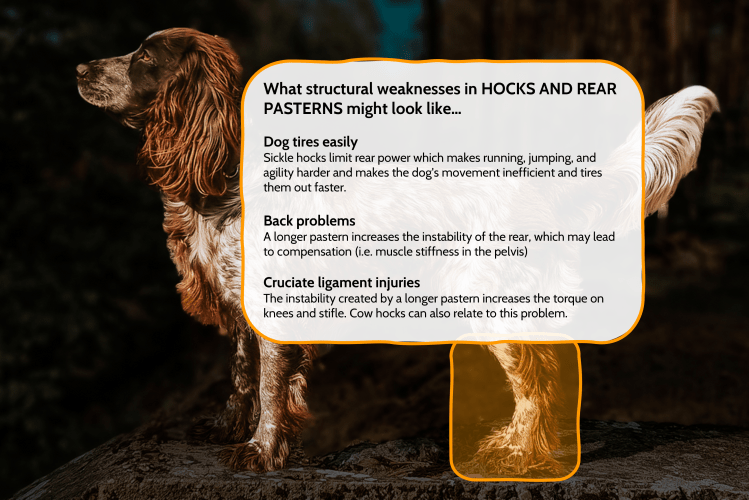

Hocks are the cornerstone of the rear assembly because stable hocks are critical for balance, strong turns, and quick jumps. Proper stable, well let down hocks enable strength, speed, and agility that form the foundation of high performance rear drive and soundness.

Hock joint: Well marked, lean, without protuberances, with well pronounced angulation.

Metatarsus (Rear pastern): Medium length, lean, smooth and elastic, vertical to the ground.

The hock refers to the rear pastern joint where the thigh meets the lower leg, and commonly means the whole rear pastern. Formed where the tibia and fibula meet the tarsus, the hock angle impacts overall hindquarter angulation. A longer pastern may make a dog better at jumping, but it increases the instability of the rear while a shorter rear pastern increases endurance and strength. The closer the hock joint is to the ground, the less power is required to move the weight.

On the other hand, cow hocks are caused by greater inside rear muscle mass, turning the hocks inward. Cow hocked dogs lack stability, increasing injury risk in sports. Dogs appearing cow-hocked while standing may have other issues creating an illusion, like overangulation. Barrel hocks are the opposite of cow hocks but also reduce stability.

Dogs with sickle hocks stand with rear pasterns slightly forward to support weak hindquarters and they typically stem from flaws like overangulation, rounded croups, or extreme hock angles. Sickle hocks limit rear power which makes running, jumping, and agility harder and makes the dog’s movement inefficient and tires them out faster..

Note: as always form follows function – slightly outward rear feet are acceptable in border collies because they help stabilize the dog in crouched work positions.

Read more on movement and gait

Evaluation of Movement—A Matter of Balance

Form Follows Function – Part 2: Canine Structure and Movement

Video – internal view of muscles – dog in motion

Downloadable guides

The Drentse Patrijshond Association of North America has excellent free knowledge packs for their breeders – you can access them here:

- Canine Terminology

- Anatomy, conformation and movement (general)

- Coat and skin

- Conformation

- Anatomy

- Angulation

- Movement

- Scientific paper on working dog structure

If you want to compare the PSM breed standard to other similar breeds, here are some options: English Cocker Spaniel, English Springer Spaniel, field spaniel, and Welsh springer as well as Deutscher Wachtelhund (German spaniel) and kleiner munsterlander from the pointing dog group.